NFL Quarterback Research: 1978-2013, Part One

This will be the first post of many discussing a massive research project I undertook following the 2013 season — I ended up with enough data, insights and factoids to fill a blog for a year.

My initial purpose was to try and make sense of Nick Foles. I own him in virtually all of my dynasties and wanted to see if I could learn anything by identifying historical quarterback comparisons to Foles and seeing what they might suggest about his future. Foles’ prospects going forward will be a post in and of itself (I think I have a pretty good answer), but for today I’m just going to explain my methodology and introduce the framework I’ll be using for subsequent posts.

To begin, I gathered three sets of data from Pro Football Reference:

- I went back into the defensive data for each year and gathered pass defense statistics for every team from 1978 to 2013. Having done that, I calculated each team’s Completion Rate against, TD Rate against, INT Rate and Sack Rate for that year.

- I did a search for all quarterback seasons from 1978-2013 for quarterbacks who entered the league after 1977 (i.e. they had a rookie season from 1978 on) and had at least 200 attempts in at least two seasons – these filters were nothing more than an effort to cut out a lot of the riffraff and cut the project down to size. This yielded 166 QBs and 938 QB seasons.

- I went to PFR and gathered the individual game logs for each of those 938 qualifying quarterback seasons — 12,754 games in all.

Having gathered all that data, the next step was to combine the game log data with the pass defense data to calculate expected Comp %, expected TD %, expected INT % and expected Sack % for each of the quarterback seasons (based on the defenses played), then compare each quarterback’s predicted totals to his actual totals for that season. Once this was done, each season had NET numbers for all four measures. A positive score indicates the quarterback performed better on that measure than an average quarterback would be expected to, and vice versa.

Because differences in the NFL’s pass-defense rules show up in the annual pass-defense numbers, these NET numbers have the advantage of being automatically adjusted for differences in era from 1978 to 2013. In other words, a 58% completion rate in an era when defenses were giving up only 54% on average is treated the same as a 65% rate when defenses are giving up 61% — both are +4%.

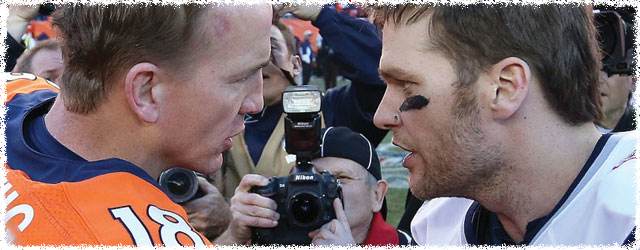

By way of an example, let’s look at Peyton Manning’s 2013. Based on the defenses he threw each pass against, his season looks like this:

Actual Comp % = 68.29%

Actual TD % = 8.35%

Actual INT % = 1.52%

Actual Sack % = 2.66%

Predicted Comp % = 62.03%

Predicted TD % = 4.56%

Predicted INT % = 2.50%

Predicted Sack % = 6.33%

NET Comp % = 6.25%

NET TD % = 3.79%

NET INT % = 0.98%

NET Sack % = 3.67%

So, having generated net numbers for our four measures for all 938 quarterback seasons, I went one step further and went back to PFR to get each quarterback’s W/L record for games started each year, and calculated his Win % for each season – that allowed me to run a regression comparing the NET numbers for Comp%, TD%, INT% and Sack% to the Win % numbers. In the end, I was able to generate a single number for each season that represents an estimate of how many games won or lost were accounted for by quarterback play that season.

This is the fun stuff.

The equation for estimating the true value of a quarterback’s season in terms of his effect on a team’s winning percentage:

- Base Win % of 50.1% +

- Net Comp % x 0.4803 +

- Net TD % x 6.2096 +

- Net INT % x 3.9414 +

- Net Sack % x 1.0968

All of the measurements were extremely significant on their own, but they also correlate strongly with each other and Comp % was close to irrelevant once you had the TD, INT and Sack numbers. Still, I kept it in the equation since it boosted the correlation slightly, and makes intuitive sense. It’s nice that the base win % for a dead average quarterback — one with a score of 0% on each of the four measures — is almost exactly 50%. That’s as it should be.

Going back to Peyton Manning’s 2013 by way of an example, here’s how those numbers are actually used to generate an estimate of the wins that Manning was worth this year:

- Base Win % of 50.1%, plus

- NET Comp % of +6.25% x .4803, plus

- NET TD % of +3.79% x 6.2096, plus

- NET INT % +0.98% x 3.9414, plus

- NET Sack % +3.67% x 1.0968

This yields a total of 84.4%. So Manning’s expected win % is 34.4% above average (50%). Multiplying 34.4% by 16 games gives you an expected +5.5 wins on the season (4th best since 1978). In other words, Manning’s 2013 performance alone turns an 8-8 team into a 13.5 win team, on average.

For stats nerds, the AR^2 on those metrics vs win percentage is 31.7%, which suggests that on average, quarterbacks are responsible for almost one-third of a team’s wins and losses. An outsized number, to be sure — but it does explain why the best quarterbacks don’t always win and why average quarterbacks sometimes do. Two-thirds of the team’s performance comes from other areas.

A caveat… it would be more accurate to say “QB Play” than to consider only the individual quarterbacks in this discussion. Scheme and surrounding personnel do matter — something I hope to show by looking at the quarterbacks behind the 1980s Hogs and possibly Jake Plummer under Shanahan. But it’s simpler to point to the quarterback as shorthand, and in the real world the quarterbacks reap most of the fame and fortune in any events.

Next up: we’ll take a look at the real performance of the 2013 quarterbacks. All this information should give us all an idea of just how good that signal caller we’re building our dynasty teams around really is.

- Beating the NFL Draft: Part Three - April 15, 2016

- Beating the NFL Draft: Part Two - April 14, 2016

- Beating the NFL Draft: Part One - April 13, 2016