What Are Vacated Targets and Why Do They Matter?

When players leave or are not available for the season, the volume they had the previous year is often referred to as missing or ‘vacated’. I’ve tracked it myself and Rotoworld’s John Daigle (@notJDaigle), a smart titan of our little game, is on the case every year not just tracking vacated targets but air yards and more.

I’ve been arguing against the concept of vacated volume for a while. To be clear, it’s not because I think the data is useless. One way I try to learn is to take a position as far as I can until it breaks or doesn’t. I’ve been doing this with vacated volume and I have concluded that vacated targets may be overused and misunderstood.

The main reason I’m inclined to argue is that the evidence in support of vacated targets always seems to rest on one specific example or another. But there’s always another example that contradicts it. Chris Godwin broke out with 235 “vacated” targets. But so did AJ Brown with 102 “vacated” targets. What’s the average? Is 102 high?

I think “vacated” volume might be a dynasty narrative – more hoped true than proven to b.

To take a look, I asked Addison Hayes (@amazehayes_), the maker of all a lot of DLF’s new apps and graphs, to send over seasonal data and I tracked “vacated” volume since 2007 along with breakout players.

Some Basics

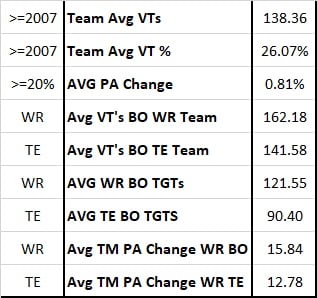

- On average, teams have vacated around 138 targets from one season to the next since 2007. The average complete loss of targets is around 26% from the year before.

- Teams that see a wide receiver breakout (finished in the top 24 for the first time in PPR scoring) average 162 vacated targets. For a tight end breakout (finished in the top 12 for the first time in PPR scoring), that number was 141 vacated targets.

- TE breakouts since 2007 average 90 targets for their stat line and wide receiver breakouts average 121 targets.

- Teams with breakout players average the same level of passing attempts from the year before with very marginal increases (15 more passing attempts for wide receiver teams and 12 for tight end teams).

The most common team situation for a breakout player is when the team has lost an average amount of volume from the year before.

Tight ends have the highest rate of breaking out on those teams. However, the rate of breakout players is higher for the wide receiver position on teams with higher levels of vacated targets, even if most breakouts occurred on average or below-average levels of vacated targets.

Them’s* the facts, now let’s deal with them. (*sic)

Mark Andrews, TE BAL and Darren Waller, TE LV

No wide receiver broke out in Baltimore last year, despite 233 (or 51% of the team’s) “vacated” targets. But Mark Andrews did – on 98 targets. Darren Waller also broke out in 2019 on a team that “vacated” a lot of its volume, over 65% between 2018 and 2019.

Either way, it seems like evidence that vacated targets helped Andrews. However, we also know that, typically, tight ends breakout on average-level volume losses. Baltimore also threw over 100 times less in 2019 than in 2018, so presumably, those other targets decided to “vacate” to an island with a mojito for a while and will be back shortly.

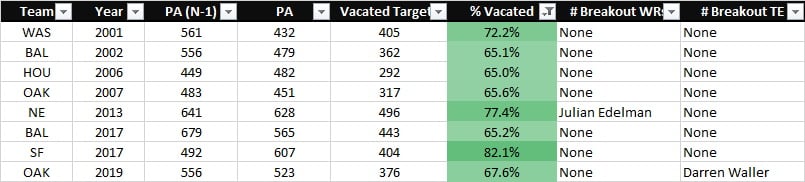

When I look at all five teams who “vacated” similar volume to Oakland (now Las Vegas) since 2007, and Waller is the only tight end to break out from those teams. Julian Edelman did also broke out at WR after New England vacated over 70%. Still, if this “missing” volume was the cause, wouldn’t you expect a better hit rate than that on teams that vacated so much volume?

(In case you’re wondering, I didn’t’ track breakout players before 2007, so I have to ignore the teams before that date.)

When I dug further and used Andrews’ team vacated targets of over 50%, I found 33 teams (since 2007). But with that expanse, we only add one more tight end breakout – Charles Clay in 2013.

On that same list, 11 breakout wide receivers showed up. That’s nice, but is it really enough? These teams vacated over half their volume – shouldn’t this work better? It seems odd to only see a 30% hit rate on this fairly rare level of vacated volume. For comparison, since 2007, 50% of wide receivers drafted in the first round have had a top-24 season.

When I look through the list of breakouts, there are other questions. DeVante Parker in 2019 is one of those 11 wide receiver breakouts. But why did he break out in 2019 with 53% of the volume vacated and not in 2018 when 51% of the team’s targets were vacated? Or in 2017 when 18% went missing, or in 2016 when 28% went walk-about?

I think this is a good indication that breakouts have more to do with – and are easier to identify through – good players and their career arcs than good absences. But let’s keep looking.

Passing volume

Since 2007, the top-scoring wide receiver from a team has joined another team the next year 52 times. 28 of those teams passed less the following year, 24 of those teams passed more after the player left. Five passed for more than 100 times less, four passed more 100 times more.

If that seems simplistic. It’s because I couldn’t find any deep research on this topic so I’m starting from the beginning. In general, a team is as likely to lose passing attempts as it is to gain them after trading their “best” wide receiver from the year before.

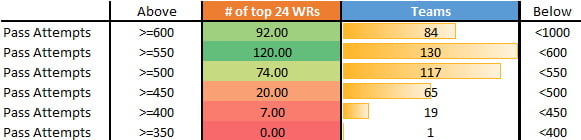

When looking at breakout wide receivers, teams passed more than they did the year before 61% of the time (out of 93 breakout wide receiver seasons since 2007).

Passing volume is relatively consistent from one year to another on a team level. However, that doesn’t mean we don’t see significant shifts, or that maintaining volume also doesn’t necessitate a new breakout player. Most of the time, even when the volume stays consistent, the targets just filter out and disperse amongst the team with little fantasy effect.

If we just used the average passing attempts for all teams between 2018 and 2015 to predict passing attempts in 2019, our average error would have been -0.46 (basically zero), but, of course, we would have had Atlanta passing for 122 times less than they did in 2019 and Baltimore passing for 160 times more. Interestingly Atlanta was only “missing” 85 targets coming into last season.

Now, why is that relevant? Mainly because it’s the best case for “vacated” volume on a year-to-year basis. But it is also the worst.

We shouldn’t think of passing attempts as synonymous with targets. Player talent has a lot to do with how passing attempts flow to create targets. In other words, not every team has a player with a 29% target share. Sterling Shepard and Tyler Boyd do not become Odell Beckham and AJ Green. And if we shift our focus away from breakouts, we see more top-24 wide receivers coming from average-level passing volume. Although, again, the rate is higher on higher passing offenses.

So, how do vacated targets fit into this broader picture, and can they help us find breakout players?

Breakout players and “Vacated” volume

Do vacated targets make breakouts easier?

I’m honestly not sure how to describe “easier.” I say with confidence that the “best” breakouts have occurred across the spectrum. Davante Adams broke out with 114 vacated targets, Jarvis Landry with 244, Antonio Brown with barely 57, Demaryius Thomas with 247, AJ Brown with 102, Tyreek Hill with 26, Vincent Jackson with 22.

The quality of the player doesn’t seem to be necessarily lower, (therefore the breakout was easier?), on teams with few missing targets.

How about in difficult, maybe compressed, target share situations?

Demaryius Thomas and Eric Decker both broke out in 2012 in Denver with 247 vacated targets. But Randall Cobb and James Jones both had their first top-24 seasons in the same year with Green Bay after the team lost only 28 targets.

Adam Thielen and Stefon Diggs broke out together, on the same team, in the same year, with 185 missing targets. The team technically “added targets” that year as well since Michael Floyd, Blake Bell, and Latavius Murray all joined the team. And I haven’t even pointed out that “added” targets are another component to vacated targets which rarely get talked about (but you can find in my data set).

So, do vacated targets make breakouts easier? It doesn’t appear so. And the level of breakout doesn’t seem to relate to the amount of opportunity “left lying around” either.

But this also isn’t the whole story.

In 2012, Tampa Bay “vacated” 47% of their targets from the year before. No breakout happened, but the recently-acquired Vincent Jackson did continue his career in which he’d already had three 1,000 yard seasons. In Tampa, he racked up 147 targets for 26% of the targets.

Did he fit in the offense because the volume was vacated from the year before? I think Jackson was just a good player and he did what the team brought him in to do. I don’t think it would have been different is every player from the year before had stayed on the payroll. Jackson was better. But it does help point out that breakouts aren’t the only players who could be taking targets, this could affect my “rate” stats above.

More context: In 2015, Tampa Bay vacated 53% of its targets and Mike Evans broke out in his second year. In 2019, the same team vacated 37% of its targets and Chris Godwin broke out, as we know.

But… what about San Diego when they lost Vincent Jackson to Tampa Bay? They had vacated over 50% of their targets, and no breakout player emerged the next season. Instead, they had to wait until 2013 when Keenan Allen broke out as a rookie with 105 targets. The team had lost 35% of its target from the year before in 2013.

So, looking back across Tampa’s history of vacated targets, was Godwin’s 2019 breakout fueled by the loss of Adam Humphries and DeSean Jackson? Or is he just another good player?

Let me ask you this: do you think the team let Jackson and Humphries go to make room for Chris Godwin, who they felt was good?

Vacated targets, in my opinion, seem to reflect the intent of the team, a lot more than the quality of the players on the depth chart. But our reading of that intent is as flawed and uncertain as our ability to read anyone else’s mind. Added to that, we have the problem that teams aren’t always going to get it right, no matter what they intend.

But the targets? They aren’t waiting, they have to be earned, and created, by the players on the field.

Do Vacated Targets Matter?

Sure. It’s hard to look at the breakout rates on teams with extreme levels of missing opportunity and not think it matters. But it doesn’t tell us who may breakout, and it doesn’t matter more than the player’s other indicators, as far as I can tell.

Is it a good idea to look at players on the depth chart for teams “missing” a lot of targets? Sure. But we should check for players showing positive indicators first, which means we should already know any interesting players on those depth charts. Plenty of players break out with average or below-average volume, so why not focus more on that than the higher rate where most breakouts don’t happen?

Godwin was a highly-drafted (and rated) wide receiver entering his second year on a high-level passing offense who precisely no serious dynasty player should have started to undervalue, for example.

It wouldn’t have hurt to highlight him. Sure. But if we think of it as an indicative statistic, would it also have pushed you away from Landry, who also landed inside the top 12 (again) last year coincidentally, with Beckham added to the depth chart?

If vacated targets are only useful when they work and not when they don’t, it’s the intellectual equivalent of suggesting people should just “draft good players”.

I think there is utility in the data. I hope more people look, explore and challenge the idea of where targets come from to find out if it can add, instead of confusing and obscuring good players on teams that haven’t vacated volume.

Click here to see the data I used if you’d like to try it.

Thanks for checking this article out, you can find me on Twitter if you want to chat about it, or in the comment section below.

- Peter Howard: Dynasty Fantasy Football Superflex Rankings Explained - March 6, 2024

- Dynasty Target and Regression Trends: Week 15 - December 23, 2023

- Dynasty Target and Regression Trends: Week 14 - December 16, 2023