What Should You Do with Ronald Jones in Dynasty Leagues?

There are not many players like Ronald Jones. At 5’11 and 205 pounds, his size alone makes him an atypical running back in the NFL, with a height-weight ratio that places him in the 20th percentile among backs drafted since 2007. His lack of demonstrated pass-catching ability also is rare: the career-best 4.3% target share he left USC with is just a 16th-percentile mark, and adjusting for total offensive involvement (his high-mark college Dominator Rating of 33.4% is impressive) means that contributing in the passing game projects to be just a seventh-percentile component of Jones’ total NFL role, according to his 12.9 Satellite Score.

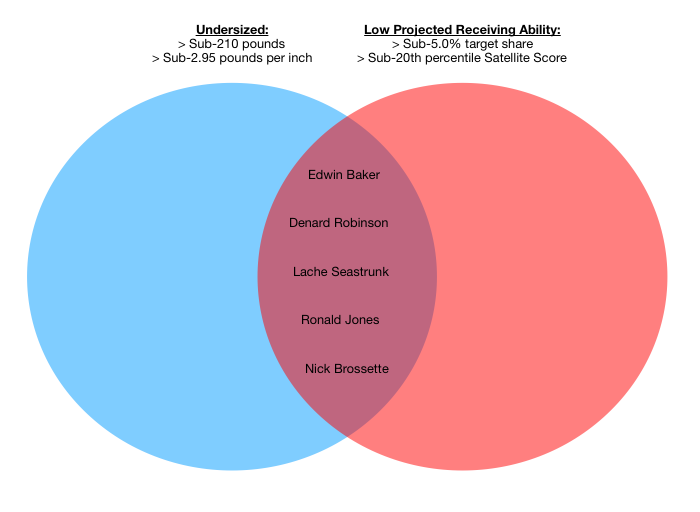

The intersecting portion of the Venn Diagram of these two elements of Jones’ profile — his size and his receiving chops — is populated by only five players (since 2007):

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

This group, which along with Jones is made up of one college quarterback in Denard Robinson, one 2019 undrafted free agent in Nick Brossette, and two late-round flameouts in Edwin Baker and Lache Seastrunk, is not an encouraging collection of comps for Jones’ outlook as a fantasy producer.

Seastrunk never touched the ball in an NFL game, and while Robinson was a decent role player for several years, he averaged just six opportunities (carries plus targets) per game for his career. Baker is actually the most volume-heavy back on this list from a per-game standpoint, as he averaged 10.3 opportunities over his just nine career appearances as a pro. Players with the small size and lack of receiving chops combo of a player like Jones have not historically operated in high-volume roles in the NFL.

In fairness to Jones, he was a substantially better college player than the other runners represented on the above diagram. His Dominator Rating as a Trojan is a 76th-percentile mark, while Brossette’s 53rd-percentile Rating is the best of the rest of the players listed (Robinson finished sixth in Heisman voting as a sophomore while playing quarterback, but evaluated as a rusher/receiver, his contributions produce a 51st-percentile Dominator Rating).

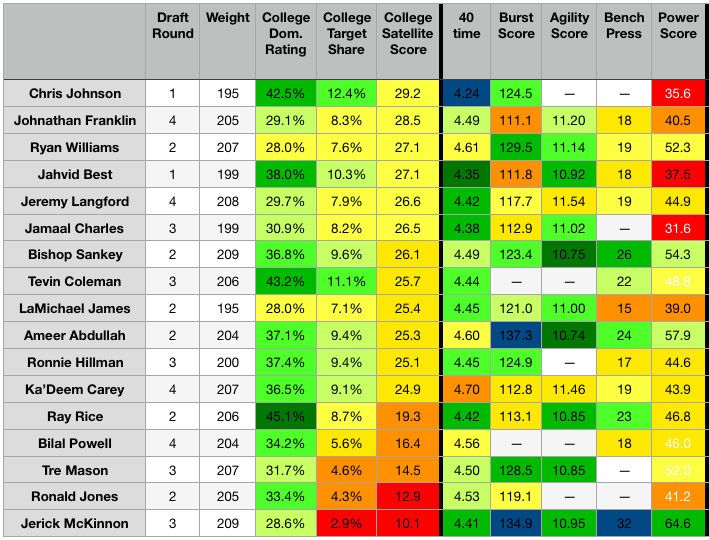

Based on quality of college production and draft capital spent to acquire them, Jones is comparable to players like Ronnie Hillman, Bilal Powell, Bishop Sankey, Jamaal Charles, and Ameer Abdullah, smaller runners who were good college players that went on to be selected before the later rounds of the NFL Draft. Even these comps give Jones more credit than he deserves for contributing in the passing game, though:

Filtering the database to include only sub-210 pound players who posted a Dominator Rating above the 60th percentile, with a below-average Satellite Score, and who were selected in the first four rounds of the Draft produces the above group of potential Jones comps (sorted by Satellite Score).

Other than Jerick McKinnon, who like Robinson played quarterback in college, Jones has the worst collegiate receiving profile of any player listed. Assuming that receiving ability matters for a smaller back (and I believe it does — the players in this group who can be considered NFL successes all proved to be quality professional pass-catchers, while the JAGs and flameouts largely did not), and given that it’s unlikely that Jones becomes a good contributor in that area considering his putrid receiving profile, it’s difficult to reasonably compare him to some of the more productive players in this group.

His athleticism doesn’t separate him here either. Even among players of similar size and with comparable college production, athletic talent, and draft capital profiles, there are almost no good historical matches to the kind of prospect that Jones was from a skill-set and potential role standpoint.

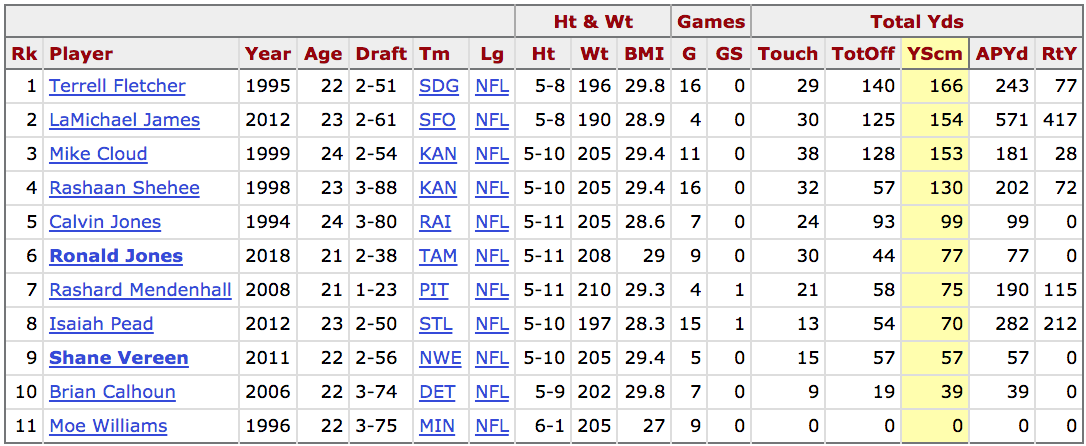

We all know that Jones busted in spectacular fashion in his first year as a professional football player. Suiting up in just nine games for the Buccaneers, he touched the ball 30 times and gained 77 yards on the season. In doing so, he joined a select group of highly-drafted runners who contributed virtually nothing of value to their teams as rookies:

Sorted by yards from scrimmage, this Pro Football Reference query includes every running back drafted in the first three rounds since 1993 (using the implementation of free agency as a pretty arbitrary starting point for the “modern” NFL) who weighed no more than 210 pounds and played in at least four games in his rookie season while posting less than 200 yards from scrimmage.

Of these 11 players, six of them spent their first year stuck behind a quality and/or established starter on the depth chart (Terrell Fletcher behind Natrone Means, LaMichael James behind Frank Gore, Rashard Mendenhall behind Willie Parker, Isaiah Pead behind Steven Jackson, Brian Calhoun behind Kevin Jones, and Moe Williams behind Robert Smith — Jones failed to wrench playing time away from Peyton Barber and Jacquizz Rodgers). Eight of them failed to record a single season with at least 800 yards from scrimmage during their respective careers. Only Mendenhall, Vereen, and Williams out of this group can reasonably be considered successful NFL players, and whether or not they set a precedent for us to project a player like Jones for success is questionable.

Identifying the exact reason that Jones failed to produce as a first-year pro is likely impossible. Perhaps he had difficulty learning the playbook. Perhaps he struggled to pick up pass protection concepts in practice. Perhaps he had a hard time making the mental and emotional transition to life as a professional athlete. There are many intangible and unquantifiable possible explanations for Jones’ poor rookie season.

There are also factors we can measure, though, and while I didn’t expect Jones to be a complete non-factor as a rookie, I believe he failed as a rookie for the same reasons for which I was not a fan of him as a prospect: he doesn’t have the requisite size of a high-volume NFL rusher, and he doesn’t have the requisite receiving acumen of a quality NFL pass-catcher. If Jones’ failure was indeed due to his inability to fit into a role in a professional backfield, then identifying other players who succeeded after showing similar inability as young players is a useful exercise.

Unfortunately for Jones, the three historical examples generated by the query are dubious matches to his particular brand of year one flameout. Though Pro Football Reference lists him at 210 pounds, Mendenhall weighed in at 225 at his Combine. He was a bigger, faster, stronger player than Jones, and much more suited to heavy early-down work as a rusher. Any projectable path to success for Jones cannot be comparable to Mendenhall’s, just given the vast difference between the two physically.

Vereen has a more similar body type and athleticism profile to Jones, but his ability as a pass-catcher was infinitely better regarded during his time as a prospect than was Jones’ (Vereen earned an 84th-percentile target share in college, per Player Profiler), and Vereen proved to be capable in that area as a professional. He is not a good play-style comparison to Jones either.

Moe Williams (a player you might recognize as the receiving end of this Randy Moss lateral) is the most interesting query result here. Athletic testing data and college target numbers are not as reliable for players drafted as long ago as he was, but he offers a combination of college receiving production (31 receptions in his final two seasons) and body type (a 2.87 pounds per inch ratio) that is about as close to Jones’ as you will find (Jones recorded 23 receptions in his final two college seasons and carries 2.89 pounds per inch on his frame).

Williams spent much of his time as a pro sharing a backfield in Minnesota with other runners like Onterrio Smith and Michael Bennett, but he did post a 65-reception, 1300-all purpose yard, eight-touchdown campaign in his age-29 season in 2003. The incompleteness of Williams’ prospect profile makes him a hard sell as a clean comparison to Jones, but he sets the strongest precedent for a player to bounce back after a Jones-like rookie season.

While Jones’ failure to supplant the JAG-y, undrafted Barber and a career backup in Rodgers during his first season is a black mark on his resumé, Tampa Bay’s decision (as of now) to not bring in another running back via either free agency or the Draft means that in order to earn a role in the offense as a sophomore, he’ll only need to supplant the JAG-y, undrafted Barber and career backup in Rodgers. It’s not a daunting task.

If he’s able to do now what he wasn’t able to do a year ago, Jones will be the beneficiary of an overall offensive attack that looks to be one of the more dynamic in the league, surrounded by great pass-catching talents like Mike Evans, Chris Godwin, and OJ Howard, and led by a successful coach in Bruce Arians and a former first overall pick at quarterback in Jameis Winston. Situation is often more important than talent in fantasy football, and the situation there for Jones’ taking looks to be a good one.

In regards to his talent, the beacon of hope is that he will still be just 22 years old at the start of the 2019 season. The most successful player in our query is Mendenhall, himself a former 21-year old rookie who turned his career around after a slow start. At his relatively young age, it’s possible that Jones is not a finished product.

I’m not one to base my evaluations of players on hopes and dreams, and the closest historical examples of guys who resemble the kind of player that Jones is right now are not encouraging. There are plenty of running backs who have succeeded in the NFL with less-than-ideal size. There are plenty who have succeeded after entering the league with one-dimensional skill-sets. There are few who have succeeded after face-planting in their rookie seasons.

The intersection of that three-circled Venn Diagram is populated only by Moe Williams, and even his inclusion is suspect given the lack of reliable information from which to evaluate him as a prospect. Ronald Jones was a good college player, but important elements of his profile indicated that he’d have a hard time finding a niche in the NFL, and his rookie campaign validated those concerns. He could yet prove to be a quality professional running back, but if that means he’s the next Bilal Powell or Moe Williams, as the best historical comps would suggest, is it really worth playing the long odds? Get out while you still can.

[/am4show]

- 2019 Summer Sleeper: Tennessee Titans - July 31, 2019

- Derrick Henry: Remember The Titan - May 28, 2019

- What Should You Do with Ronald Jones in Dynasty Leagues? - May 11, 2019