Tracking the 2017 Rookie Running Back Class: Joe Mixon

This article is the second installment of a series in which I use my Observational Rushing Numbers to shed light on just how good the 2017 rookie running backs were at carrying the ball. You can find each previous article about these numbers on the series’s hub, including a similar article about Christian McCaffrey.

For myself and most others, Joe Mixon was a member of 2017’s incredible top tier of rookie talents, placing sixth in both my final running back/wide receiver talent rankings and DLF’s March 2017 rookie ADP. The dynasty community saw him fall to, in my eyes, one of the very worst landing spots (due to a poor offensive line, Giovani Bernard, Jeremy Hill at the goal line, and Andy Dalton at quarterback) during the NFL Draft.

But after Mike Williams’s injury issues came further into the light and Dalvin Cook slipped in the Draft due to an awful Combine performance and off-the-field issues, Mixon actually rose two spots in DLF ADP. It’s unclear whether the rationale in moving him up was that his value actually improved, or that it merely dropped less than Cook’s and Williams’s. Either way, Mixon’s 3.5 yards per carry mark was about as poor as part of the fantasy world (myself included) expected, but he made up for some of that inefficiency with a surprising 212 intended touches in 14 games.

The dynasty community’s reaction to that stat line reveals how drafters probably felt in summer 2017 and how they certainly feel now about Joe Mixon on the field. Much like Christian McCaffrey, Mixon did not see his value drop — if anything, it increased to a second-round startup pick — which indicates that there was no market correction, and thus that the Bengal was expected to have an inefficient 2017. Since that’s the case, and because that 3.5 Y/C is so poor, we can logically assume that the overarching community still loves Mixon’s talent, just not the current situation — that poor blocking and other surrounding factors hurt his efficiency, not his own talent.

Rushing efficiency is just one variable of a few (volume and receiving ability are the other two major players) when it comes to a back’s rushing productivity, and some might argue that it doesn’t matter to much of an extent, but I’d disagree: Given how replaceable NFL backs have become, players aren’t going to sustain their workloads from year to year if they don’t provide teams with above-average productivity. Sometimes, that happens even when it’s the O-line’s fault, and not their own. In other words, rushing efficiency serves as one crucial determinant of future volume. Thus, when evaluating young back’s seasons, it’s vital to inspect why they were or were not producing well with the opportunities they got — what yards per carry measures.

Yards per carry is a tricky equation defined roughly equally by two separate variables (running back and blocking), so we can’t be sure that the community’s assumption is really the case without looking further. Much like I did with McCaffrey, I’ll be using this space to take that further look, using my Observational Rushing Numbers (ORNs) to see just how effective Mixon and his offensive line were in 2017, and how much blame for the low Y/C each side is really responsible for.

(I’ve taken these tracking stats from Weeks 1-14 for each rookie running back with at least 75 carries. If you’re wondering what any of the stats mean in a fuller sense, check the series glossary.)

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

At a glance

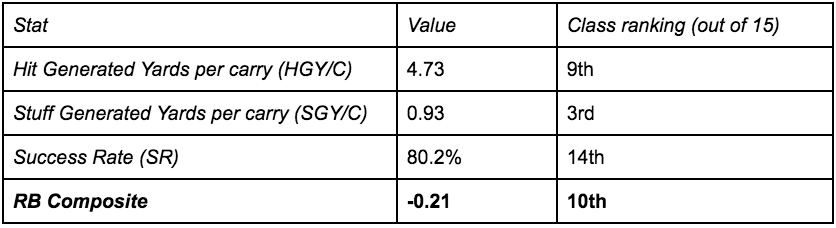

Four Big Stats:

Mixon’s overall numbers look a lot like McCaffrey’s — below-average explosiveness (what HGY/C measures), great limited-space creativity (SGY/C), and a striking inability to hit holes (SR) — and so too do his supporting stats, to a limited extent. The primary difference is that by generating an extra half-yard per carry when he was in daylight, Mixon’s HGY/C measure was much closer to average than McCaffrey’s. As a result, Mixon was less of an overall net-negative to the yards per carry equation than McCaffrey (what RB Composite — a standardized combination of the first three stats — measures).

If you haven’t noticed yet, the comparison between Mixon and McCaffrey is going to be a theme here. Both had less-than-great rushing efficiency, both have sustained their respective value and sit in the second round of DLF ADP, both had similar highs and lows, both have similar reasons to be optimistic about their individual lows heading into the future, and both still have concerning lows that lie outside of their control. Having spoken about those first three points, I’ll now dig into the last two.

Success Rate

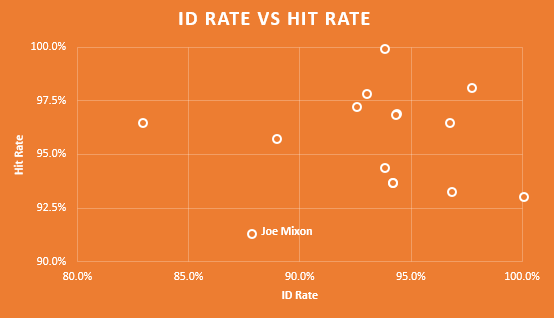

Identification Rate (ID Rate — how often a player finds the hole) and Hit Rate (how often a player makes it through a hole they’ve found) are the two stats that make up Success Rate. Similar to McCaffrey, Mixon blew roughly one-fifth of the opportunities his offensive line provided, but unfortunately, there’s less reason for optimism in Mixon’s case. For McCaffrey, his ID Rate was the only problem, which was probably so low because of a rookie learning curve — in the second half of his games, his Success Rate reached a perfectly healthy level. Likewise, Mixon’s ID Rate is promising in the future — it stepped up from 77% in his first seven games to over 98% in his last five games… the problem is that his Hit Rate was just as bad of a problem:

Joe Mixon struggled to find holes like McCaffrey did, but the potentially crippling blow is that he was the worst of any rookie back at getting through those that he did find. That surprised me, as Mixon might’ve had the most weakness-free skill set of any rookie back entering the NFL in 2017. Hit Rate measures a combination of quickness, agility, functional strength, and balance (primarily), and one would expect that a stat encompassing so many skills would be friendly to a back with virtually zero weaknesses. Obviously, that wasn’t the case for Mixon, so I looked back through his worse plays to figure out why. It was pretty simple: the Sooner gave up a lot of daylight to arm tackles that most backs would break.

The video shows a few of the clearest examples of Mixon’s struggles. An athlete with his stature should have no problem breaking those tackles. In order to fix his Hit Rate, Mixon must improve the balance and functional strength necessary to get through linebackers and secondary when he has a step on them — really not too much to ask. As he likely takes a sophomore (or junior) leap, I’d expect that he does so, but there’s no guarantee he gets better. Unlike McCaffrey, Mixon will have to take a further step in his own game in order to fix his Success Rate.

Hit Generated Yards

When writing about McCaffrey, I posited that his lowly 4.21 HGY/C mark was largely due to bad luck: He tied for the class’s third-highest Broken Tackles per Hit measure (BTK/Hit — broken tackles divided by every time he hit a hole) and got into the second-level at an above-average rate (generating 10 or more yards on 12% of the holes he hit — H 10+ Rate), but finished 12th out of 15 because his outlier runs weren’t nearly as big as others’, which might or might not have any bearing on how he actually played. I expected him to be much more successful at creating in daylight in the near future.

That case of improvement isn’t as great for Mixon. For one, his HGY/C mark was much closer to average than McCaffrey’s. More importantly, his H 10+ Rate (12.5%) and BTK/Hit (0.21) stats contradict each other, where he’s above average in the former but one of the class’s worst in the second. HGY/C roughly split the difference, as he finished a bit below average at generating yards in daylight. What the contradiction tells me is that there’s an opportunity for Mixon to improve the stat, again, if he actively improves as a runner.

When a player gets to the second level at an above-average rate and generates close to an average amount of yardage while barely breaking any tackles, it tells me two things: (1) The back created yardage using open-field speed and acceleration quite well. (2) The back could’ve been amazing if he combined that athleticism with shiftiness, but he didn’t. If Mixon can add better elusiveness or power (or both) to his game, he should be one of the best open-field creators in football. On paper, he’s got the raw tools to do it, with nice agility and a frame that can handle more weight.

Again, however, you should be cautious. Just because he can make that improvement, doesn’t mean he will.

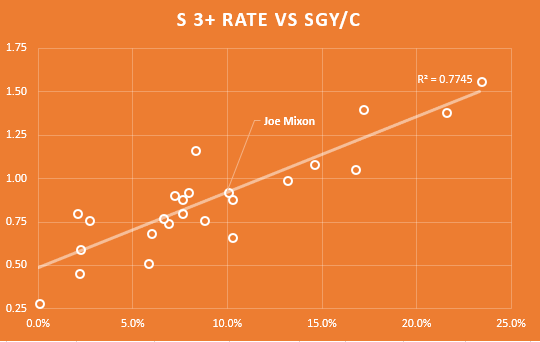

Stuff Generated Yards

A fundamental part of positively contributing to Y/C in tight confines is that a back simply ensures that he generates a few yards (to be precise, three yards) as often as possible (measured by S 3+ Rate — how often a player generates three or more yards on stuffs). Joe Mixon did that well, and thus was a huge plus on runs with nowhere to go:

Christian McCaffrey, barely over 200 pounds, was one of the class’s best at generating yardage with little room, and he did so using his quickness, decisiveness, and extremely low pad level. Mixon has a similar level of those first two, and made up for his height (which makes it tough to get leverage on tacklers when facing them head-on) with strength that allowed him to stretch for extra yardage at times. There isn’t a lot of complexity to the SGY/C equation, but that doesn’t make it any less important. Mixon highlighted his limited-space strengths and minimized his weaknesses, and should do more of the same in the future. Running behind an offensive line like the Bengals’, making the most out of nothing is pretty important.

Run blocking

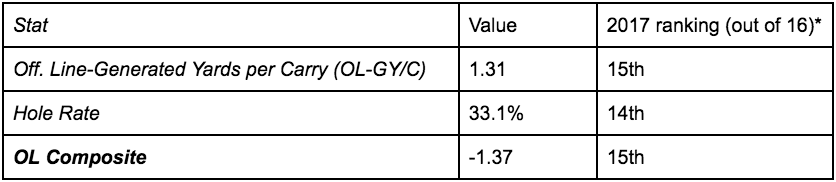

Three Big Stats:

The 2017 Cincinnati Bengals offensive line: uniformly terrible. Joe Mixon’s blocking provided him with a measly baseline of 1.31 yards on each carry (what OL-GY/C measures), worse than every unit I’ve tracked but the Colts; they could barely do better to provide Mixon with opportunities (what Hole Rate measures). The result, logically, was the second-worst offensive line I’ve tracked to this point.

The bright side is that there’s some room for optimism for this unit in 2018. Most importantly, the 2017 Bengals had 10 offensive linemen log at least one game’s worth of snaps, and it’d take a huge stroke of misfortune for the injury bug to hit that hard again. Furthermore, after this off-season’s transactions, the Bengals have three backups with multiple games of starting experience.

Those transactions will hopefully provide Cincinnati with a further injection of talent: They took center Billy Price with the 21st pick of the 2018 NFL Draft, and after acquiring left tackle Cordy Glenn in a related trade, they will (ideally) get to slot the better side of Glenn and Cedric Ogbuehi (25 starts in the last two seasons) in at left tackle.

With reasonable optimism, the losses of Russell Bodine, who’s started every Bengals game at center since being drafted in 2014, and Andre Smith, who’s logged 85 starts at tackle over nine years and filled in for Jake Fisher at times in 2017, shouldn’t offset the additions of Price and Glenn. Beyond those two, the Bengals will enjoy continuity as last year’s injuries turn into this year’s experience. The less promising angle? Cincinnati’s rostered offensive linemen combine for precisely zero Pro Bowls. There may be positive regression to the mean in store, as well as a relative increase in talent, but the ceiling still looks quite low.

For now, I’ll say the best-case scenario is a middle-of-the-pack squad, while the worst case looks a lot like 2017. It could be worse, I guess?

*I have tracked some veteran RBs already, and some teams have multiple rookies with over 75 carries, so there will be a difference between the rookie RB class’s 15 members and the amount of offensive lines being ranked.

Conclusion

Dynasty owners are placing a lot of faith in the idea that Joe Mixon is as talented as was advertised during draft time last year and that his surroundings should improve in time. With the right degree of optimism, that is the case indeed. With better functional strength, balance, and power or elusiveness, Mixon provides everything that you could ask from the running back’s side of the yards per carry equation. The offensive line almost certainly won’t get worse, and there’s reason to expect it to improve a good amount.

With the right degree of pessimism, however, that faith could be misplaced. Just because a player can get better doesn’t mean that he will. Mixon was much more elusive in college than in 2017, which is a glass half-empty/half-full proposition. On the other side of the situation, the Bengals have proven that the floor is about as low as it can get, Price has played zero NFL snaps and has the only possibly high ceiling of the bunch, and even then, it’s hard to see him immediately being better than a player who has started 64 consecutive games.

All that said, if I owned Mixon, I wouldn’t sell him unless I were getting full value. Young running backs perceived to be talented and running behind poor blocking might have better-insulated value than any other dynasty assets. Mixon should have a few years to improve his game, a perfectly plausible scenario given that he’s entering just his second year, and shouldn’t actually see his value fall for two or three years (barring extenuating circumstances). In the meantime, he added almost 300 yards in 14 games as a rookie, and should probably continue to add somewhat of a floor in the passing game.

It’s hard to see Mixon flaming out in the near future, which is basically the only way he loses value between now and 2019. If you can buy him low and have a roster strong enough to allocate that much capital to an asset that might not produce much this year or next, I’d be all over picking him up.

[/am4show]

- 2024 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Drafts: A View from the 1.03 - April 21, 2024

- Devy Fantasy Football: Top Five Quarterbacks - August 22, 2022

- 2022 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Prospect: Drake London, WR USC - April 16, 2022