IDP Heuristics: An Easy Way to Beat the System

As the world hurtles forward, we’ve uncovered more information about almost everything. We know more about what people are, what they do, what they say and even what they think than ever before. And not just by a little bit – by orders of magnitude. We are well and truly into the realms of Big Data.

The football world (and fantasy in particular) has dived headfirst into this. The NFL has produced advanced stats, Pro Football Focus has turned into a juggernaut and the whole fantasy world can spout numbers like yards per carry and sack rate and yards created and air yards on demand.

There is more data and more information than ever before.

And this can only be a good thing, surely? Football is complex. There are 22 players on the field all doing different things, the coaches are involved on a play-by-play basis while deception and misdirection are major parts of the game. Complex problems need complex solutions which is why we as a community have busily developed advanced metrics to better describe and predict what is happening.

Which brings us to a science called heuristics. Heuristics claims that actually complex data can often not be the best solution to complex problems. In fact, sometimes simplicity gives a better and more useful answer.

An example is a returner fielding a punt. Calculating trajectories of a moving ball is hard. You need to account for the speed it’s travelling, the angle, the spin, the wind conditions and several other factors. Mathematically it’s a nightmare. But every week we see returners unerringly underneath the ball. They’re not out there doing difficult math as the ball falls. They use a simple heuristic.

If you run towards a falling ball and ensure the angle of the ball remains the same, you’ll arrive at the same time as the ball. We learn to do this unconsciously when we’re kids and do it automatically. Heuristics enable us to do complicated things simply.

This is due to a number of factors but one of the most common is overfitting. This is a phenomenon that arises when we try so hard to model data that our model becomes less useful as a predictive tool. We build models that work on so many variables that they become difficult to use. Unwieldy and overly complicated. They take a huge amount of time to build and maintain and lose their usefulness.

In this writer’s own favored field, this is definitely a problem. Modelling defensive players requires a few basic bits of information. You need to know how much a player will play, what position he plays, how he’s used (how much time does he rush the passer or drop into coverage), what sort of scheme he plays in, etc. It does a good job and is useful in the off-season to give a good idea of which players are likely to be productive in the coming season.

But that’s not quite enough.

The biggest problem is that players get hurt, lose favor and emerge all the time. As we always say: “things change fast in IDP”. This is where a complicated model falls down. After week one of the NFL season, we are always surprised by something. A player fancied to be very good was left on the bench. A star player got hurt. An unfancied rookie was used in a prime way. A complicated model involving many variables is a problem here. It takes time to update it based on the available data and more time to analyze the results. By the time it’s done, waivers have run and we’ve missed the opportunity to capitalize on the knowledge.

Hence the need for a heuristic solution. We need something easier that can be updated quickly and easily to give us actionable advice.

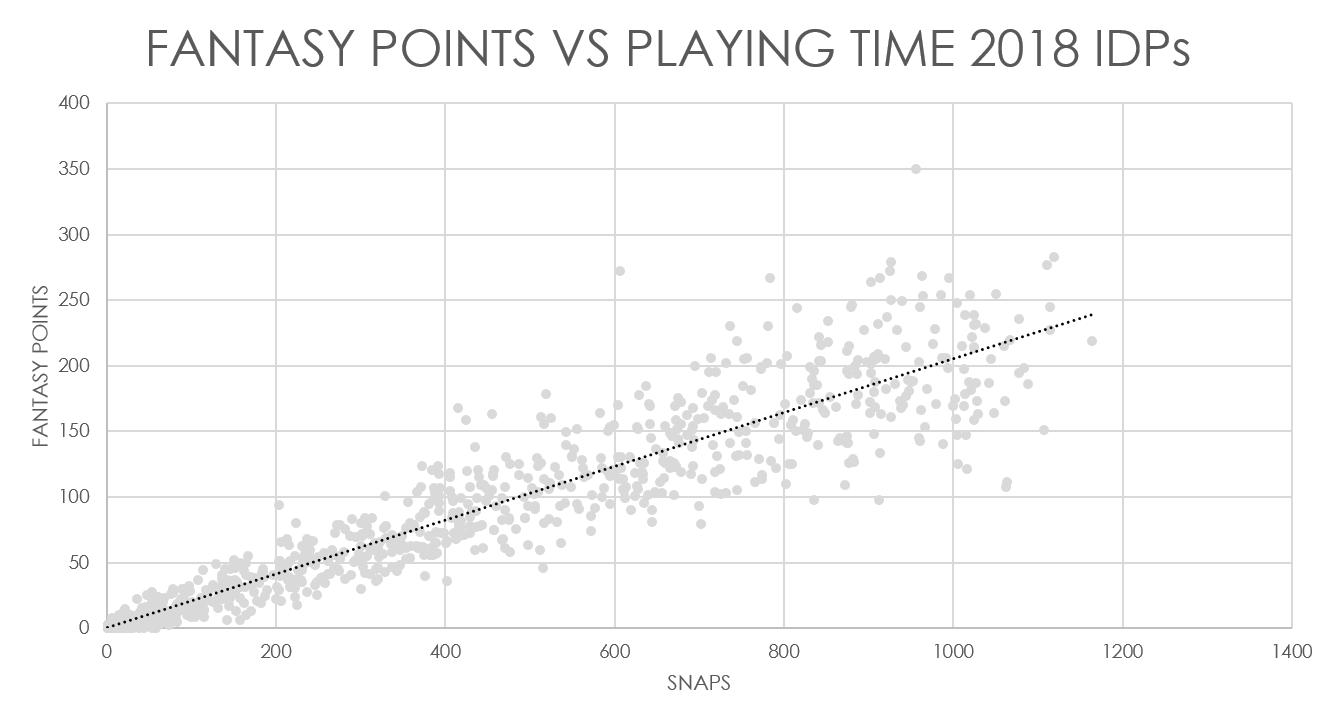

With IDPs (and a lot of football), the answer is simply playing time. There is a direct correlation between how much a player plays and how they score as a fantasy option. Here’s a chart that shows it:

This is every defensive player from 2018 listed in terms of fantasy points (using a pretty standard scoring system) and how many snaps they played. The players score differently for the actions they perform (i.e. interior defenders score more for solo tackles than corners. While corners score more for passes defended) but all players are lumped in together here.

And as you can see, there’s a strong correlation. The more you play, the more you score as a fantasy option – in general. This should come as a surprise to absolutely no one reading this. It’s intuitive and obvious. But it’s so deceptively simple it can really help us, because analyzing weekly playing time is a very quick and simple thing to do rather than updating a complex model. Our heuristic is simply that “players who play more snaps will end up scoring more fantasy points”. Simple, eh?

That seems too simple, doesn’t it? Too obvious and not complex enough? If you’re thinking that, I advise going back to the early part of this article. We think complicated systems need complicated tools – but in reality, simple tools are often better.

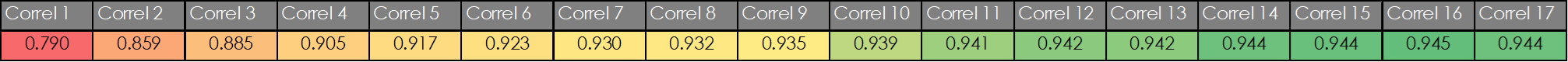

To check if this made sense, we can look back at the 2018 season and correlate snaps after each week to the final fantasy points total of each player. Here’s how that looks:

This is the weekly correlation (for all defensive players) looking at weekly cumulative snaps. I.e. how much a given player has been on the field after that many weeks.

The trend is obvious. After each week, the correlation became stronger and stronger until after the full season there was an R2 of 0.944. For those not mathematically inclined, R2 indicates the strength of a relationship. If the R2 for a given set of data is 1.00 then there is a perfect relationship. The closer to 1.00 it is the more we can be confident that the two numbers correlate.

It makes sense it rises because by week 17, the players who’ve been on the field more have had the chance to pile up more stats. Early in the season, there’s plenty of time for players to get hurt or be dropped. So, the players with the most snaps after week one do not correlate that strongly to the total fantasy points they scored in 2018.

For example, after week one of 2018, Eric Rowe and Deone Bucannon had both played a lot. But neither ended up having a good season.

As we saw in the chart earlier, we know that playing time correlates strongly with fantasy points, but this data shows us that even after week one, the link is relatively high. An R2 of 0.790 is much higher than the link between touches and touchdowns, for example.

This proves we have a viable heuristic. Instead of slaving over a model every week with a dozen inputs and tweaks, if we were simply to optimize our teams based on the IDPs with the most snaps we could be very confident we’d end with a productive team.

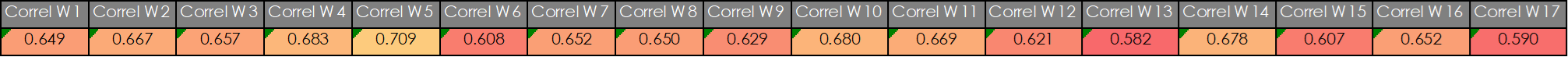

That poses another question though: “If snaps are so indicative, why can’t we just score defensive players on how much they’re on the field?”. Good question. If we simply correlate fantasy points against snaps on a weekly basis, we see this:

This is colored on the same scale as the previous table. So, you can clearly see that for each of the 17 weeks, the link between snaps and points was weaker than the overall relationship. This seems counterintuitive, doesn’t it? I’ve told you there’s a clear link between snaps and productivity. So how come snaps don’t equal points on a weekly basis?

It’s because of data granularity. Each player sees only limited snaps per week and in a dataset as big as a full season, the variance is high.

If we assume that each NFL team has 11 starters, then there are 352 starting IDPs (32 X 11). The top 352 IDPs in volume for 2-18 averaged 43 snaps per week. On a scale that small, a few extra assists or another sack or recovered fumble makes a big difference. We just don’t see a perfect correlation on a weekly basis.

This should be a big, in-season time saver in the IDP world. It doesn’t remove the need for off-season projections and it doesn’t remove the need to dig deeper into in-season stats. We’ll still need to look for players who are efficient (but not unsustainably) with their snaps. We’ll still need to watch those players to see how good they are. But it also means we can rely on fast analysis early in the week to give us a heuristic method of identifying high-value defensive players. And regular DLF subscribers will know that that is a regular weekly column.

Thanks for reading.

- Ten IDP Fantasy Football Stats You Need to Know after Week 16 - December 29, 2023

- Ten IDP Fantasy Football Stats You Need to Know after Week 15 - December 22, 2023

- Ten IDP Fantasy Football Stats You Need to Know after Week 14 - December 14, 2023