Tracking the 2017 Rookie Running Back Class: Christian McCaffrey

This article is the first installment of a series in which I use my Observational Rushing Numbers to shed light on just how good the 2017 rookie running backs were at carrying the ball. You can find each previous article about these numbers on the series’s hub, including a January article about Todd Gurley’s 2017 resurgence.

Just 12 months ago, Christian McCaffrey was a member of the 2017 rookie class’s elite: DLF’s May 2017 ADP data had him as the third-highest player taken in the class. Given a not-so-promising blocking unit and some competition with Jonathan Stewart, smart owners entered the season without expecting a great rushing stat line in 2017. Sure enough, pessimistic projections came to fruition as he put up a pedestrian 117 rushes for 435 yards, just 3.7 yards per attempt.

Dynasty players seem to have remembered those low expectations, because they haven’t let McCaffrey’s poor 2017 ball-carrying statistics hurt his value too much — he’s still a middle-second-round startup pick per DLF’s May 2018 ADP data. The reasoning is twofold: (1) With over 600 receiving yards in the regular season, he bolstered his production with nice receiving numbers in 2017 and should do similar in the future. (2) The rushing talent is there, it’s just being masked right now by poor offensive line play — which should eventually improve. Are those premises actually correct? There’s little reason to expect a downtick in future receiving production for McCaffrey, but that question gets much trickier with the latter assumption.

I’ll be using this space to answer that question using my Observational Rushing Numbers (ORNs), tracking stats that I record to quantify and separate running back play from offensive line play. I’ve taken ORNs from the first 14 regular season games of each rookie running back with at least 75 carries (in addition to some other players from this year and last). Let’s see what the stats have to say about the Panther, in comparison to the rest of the class.

(If you’re wondering what any of these stats means in a fuller sense, check the series glossary.)

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

At a glance

Four Big Stats:

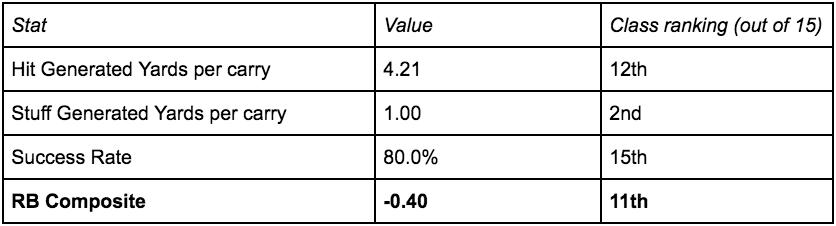

On the surface, things don’t look great for Christian McCaffrey. He finished in the bottom third in two of three Supercomposite stats (metrics that are particularly important for producing good per-carry rushing numbers): Hit Generated Yards per carry (HGY/C) and Success Rate (SR). In English, McCaffrey made it through the holes his offensive line opened for him (what SR measures) the least of any rookie back, and even when he made it there, he couldn’t do much to create (what HGY/C measures). These poor finishes led to him effectively being the 11th-best (of 15) rookie in the class when it came to purely running the ball.

However, there’s another (quite interesting) side to this story. He posted the second-best Stuff Generated Yards per carry (SGY/C) mark — the stat that measures how well someone churns out yards when there’s little to work with. That’s right — he was, effectively, the second best back at grinding out yards in tight confines. What? Surely this must be wrong; absolutely nothing about this guy’s draft profile suggested that he’d fit the “grinder who can’t hit holes or work in the open field” bill. Allow me to explain.

Success Rate

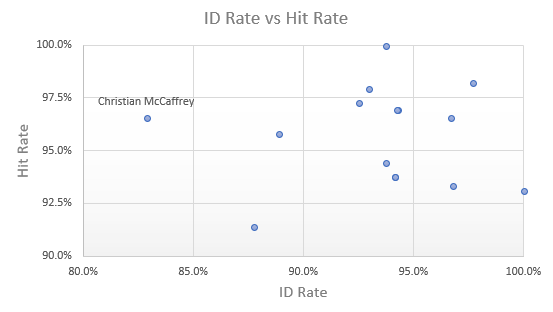

Success Rate is the combination of two underlying stats: Identification Rate (ID Rate — how often a player finds the hole) and Hit Rate (how often a player makes it through a hole they’ve found). Multiply the two together, and you get success rate. McCaffrey’s problem came with his vision. His Hit Rate was perfectly fine (96.6%, tied for seventh in the class), but at 82.9%, his ID Rate was appallingly bad — almost five percent worse than the next lowest mark:

The quickness, agility, balance, etc. that the Panther showed in college was still there; however, the vision wasn’t. There are a couple theories to explain this phenomenon, but it’s tough to say how much each contributes to this outcome.

First, lower-quality holes could have hurt his performance a bit, since the Panthers had weak run blocking and since there’s a slight relationship between Success Rate and yards generated by the offensive line (OL-GY/C).

Second, with just three games carrying the ball in double digits, he didn’t get many opportunities to settle in (and there’s some anecdotal evidence to show that settling in could lead to meaningfully better production).

Finally, the NFL moves much faster than college football, and there will be a learning curve for anyone — it just might be bigger for some rather than others.

After #watchingthegames, I subscribe to that last point the most. As I charted, there were a couple of players (McCaffrey included) who looked quite hesitant as they dipped their toes into professional football. That adjustment period seemed fairly long for McCaffrey, weighing down his season-long stats, before he came on strong to finish the season. The numbers support that notion: In his first seven games, he identified an awful two-thirds (67%) of his holes, while in his next seven, he identified 95% — a perfectly passable number. The sample size is relatively small, but both the numbers and my eyes are confident that his vision is in a much better place now.

Hit Generated Yards

It didn’t take a trained eye to see that McCaffrey was one of the most dynamic players in college football while at Stanford. How, then, did he record some of the class’s lowest creativity numbers?

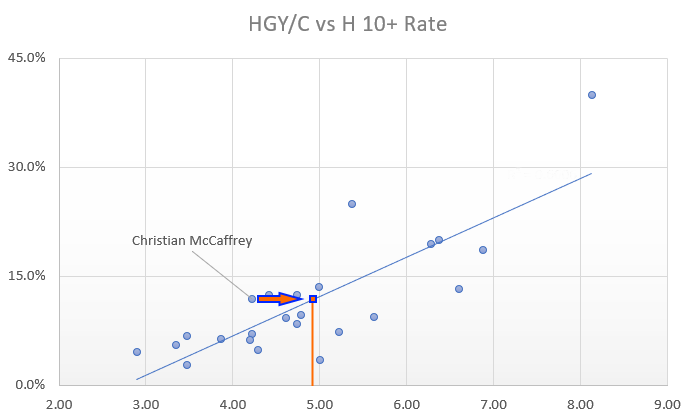

After looking through the supplementary data, I think he was just plain unlucky. There are three primary stats I look at when evaluating a back’s creativity: HGY/C, Broken Tackles per Hit (BTK/Hit — how often a runner dodges a tackler divided by the times they get into daylight), and 10-plus Hit Generated Yard Rate (H 10+ Rate — how often a runner generates at least 10 yards when hitting a hole). The relationship between these stats is good-not-great (BTK/Hit explains about half of the variance in HGY/C while H 10+ Rate explains about two-thirds), so when one of these stats is much lower than the other two, we might expect that one to rise in time. That’s just the case here.

The Panther’s 0.39 BTK/Hit is tied for third in his class, and his 12.0% H 10+ Rate is slightly above average. In other words, he was still as slippery as advertised in 2017 and perfectly capable of getting deep into the second level on his own. This leads me to think he was just unlucky. Because HGY/C is an average, it is well-influenced by outliers. McCaffrey got far fewer outlier opportunities than most of the class (his highest GY on any single carry was 14, whereas most backs have highs in the 20s and 30s), so his HGY/C mark suffered in comparison to his peers.

The other two stats — H 10+ Rate especially — are less prone to big plays, so I’d expect those two to uphold themselves much better than HGY/C in the future. In other words, I think McCaffrey will provide solid creativity and explosiveness in the future. It’s tough to say just how much he’ll improve, given that he was near the bottom of the class and thus there are many different levels of progression that could be in store, but I’ll turn to H 10+ Rate to get a better guess at where he’ll be in the near future:

We’d expect McCaffrey’s HGY/C mark to approach the trend line shown in the graph as time goes on, so a good future expectation for McCaffrey would be around 5 generated yards per hit. That’d put him at eighth in the class, so still not great, but certainly workable — before we ask the question of if he actually improves as a player.

Stuff Generated Yards

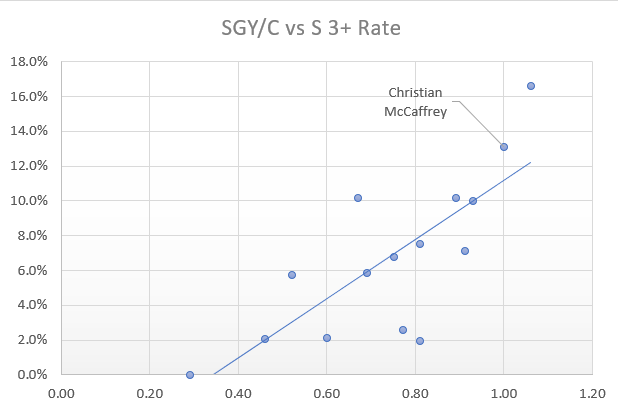

Now we get to the most pressing question: At 5-11 and 205 lbs, how on Earth was Christian McCaffrey one of the best limited-space runners? Simply put, it’s because he does the non-size-related things really well.

When I profiled McCaffrey last year, I noted how well he finished runs:

“McCaffrey does a really good job to make up for his small build in his running style. In the open field, he’s all about cutting and putting moves on tacklers, but when given no daylight, he makes a great effort to get low, drive his feet, and finish forward. For such a small guy, I think it’s a bit impressive in just how often he falls forward when being tackled by a front-seven player. His efforts turn losses into net zeroes, and three-yard gains into five-to-six yarders. These small boosts in the inside running game make him a much more viable runner up the middle.”

Fast forward a year, and McCaffrey still does really well to finish forward. With the help of his quickness, decisiveness, and lateral agility, he makes up for a lack of size by beating tacklers to the punch, which allows him to gain leverage with low pad level when running in the box and to keep running after contact when running outside. This video helps to illustrate how he uses those strengths to generate yardage without a hole:

McCaffrey doesn’t run anyone over, but he does everything well enough to be a net-positive among a group of runners who are too inconsistent — particularly with decisiveness — to be anything but a net-negative. Using it in a similar manner as H 10+ Rate above, his three-plus stuff generated yard rate (S 3+ Rate) verifies the claim:

McCaffrey claimed the second-best levels in both SGY/C and S 3+ Rate among rookies with ease. Although he’s far from the biggest back, there’s very little tangible evidence to indicate that McCaffrey can’t hold his own in short yardage.

Run blocking

Three Big Stats:

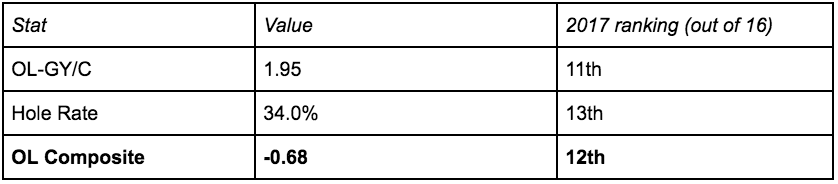

Unfortunately for McCaffrey and the rest of the Panthers offense, the blocking unit grades poorly across the board. The offensive line provides little push (what OL-GY/C measures) and few opportunities (what Hole Rate — HR — measures). The result: A similarly poor OL Composite, which combines OL-GY/C and HR to give run blocking a single-number overall rating.

Given that offensive line play is one half of the yards per carry equation, it’s very hard to be efficient when running behind a unit like Carolina’s. Sure enough, that bore itself out with McCaffrey’s 3.7 yards per attempt in 2017 (which, of course, was partially his fault too).

There’s a chance that this unit improves in 2018, similar to McCaffrey, but I wouldn’t count on it. The good news: The Panthers retain four of five offensive linemen who logged at least two-thirds of the team’s offensive snaps, as well as Ryan Kalil, a five-time Pro Bowler who missed all but six games in 2017.

On the other hand, Kalil has missed more games than he’s played in in the last two seasons, and though continuity is nice, there’s no guarantee that a bad offensive line that rolls nearly the same thing over will actually improve. That second point gets stretched further when the single departing 2017 starter was the unit’s very best: After earning First-Team All-Pro honors and becoming the highest paid guard in football this off-season, Andrew Norwell has taken his talents to Jacksonville.

Jeremiah Sirles, an undrafted free agent who’s started 15 games in four years and will be joining his third team this fall, is apparently the favorite to fill in for the $66 million man. Taylor Moton, the last pick in the second round of the 2017 draft, is the only offensive lineman the Panthers have drafted in the last three years, and currently serves as a utility guy who logged less than six percent of the team’s offensive snaps in 2017. There wasn’t much success for this line last year, its best player left, and the Panthers don’t have a great way to replace him. Yikes.

Conclusion

I feel conflicted when trying to nail down Christian McCaffrey’s dynasty value. He has a greater collection of highs and lows than most backs, and it takes a pretty close, nuanced look to really dig into those ups and downs. The positive side is clear: Everything he did in college and the draft process indicated that he should be one of the NFL’s most dangerous-yet-stead players with the ball in his hands. He continued to show that promise with awesome first-year production in the passing game in 2017.

Meanwhile, his weakest points manifested in the running game, where poor offensive line play and a disappointing performance of his own combined to allow the Stanford man just 3.7 yards per attempt. But, if you put that second point under a microscope as I’ve done, you see that his struggle was caused primarily by a lack of experience and a good bit of misfortune. The former issue was resolved in the middle of 2017, and you’d expect the latter to go away in the near future. Of course, McCaffrey was just a 21-year-old rookie last year, so it would be safe to expect him to actually improve — beyond those two factors — this year and maybe next.

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for his offensive line. The greatest hope there is that one of Norwell’s potential replacements surprises with solid play. That, combined with fully healthy seasons from Kalil and Trai Turner (who made his third consecutive Pro Bowl despite missing three games in 2017) could mean that the offensive line doesn’t really fall off, especially given its collective continuity.

If we’re being especially optimistic, then we might say that the additions of D.J. Moore and Torrey Smith (and a more healthy Curtis Samuel) could open things up for the Panthers running game, similar to what we saw happen with Todd Gurley and the Rams between 2016 and 2017. I don’t expect much of that to develop, though. Suitors for Norwell’s spot aren’t particularly inspiring, it’s hard to count on any offensive line unit to stay healthy, and a lot of the Rams’ surge can be attributed to a drastic coaching change and a sophomore leap from Jared Goff.

Altogether, I’d expect a similar year for McCaffrey in 2018 as 2017. His running back play will improve more than blocking regresses, but not to a great degree. He should still provide a nice production floor in the passing game; adding Moore and using Samuel more puts some of McCaffrey’s volume in doubt, but he should enjoy more space and per-catch efficiency as a result. In the long run, we’ll hope that the Panthers invest more in the running game. After all, two key additions to a blocking unit can flip it from bad to good and have that same positive impact on a back’s per-carry numbers.

All things considered, I think it’s correct to keep McCaffrey in the second or third round of startup ADP. He was already a great value in PPR leagues last year, provides a tidy floor that most backs can’t equal, and has real untapped upside that can be hit. Most importantly, he’s still quite young in an ascending offense that’s a couple of breaks on the offensive line away from being great. I’m willing to pay up for a talented, multipurpose back in that setting with a floor like his.

[/am4show]

- 2024 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Drafts: A View from the 1.03 - April 21, 2024

- Devy Fantasy Football: Top Five Quarterbacks - August 22, 2022

- 2022 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Prospect: Drake London, WR USC - April 16, 2022