Salary Cap Confidential: Cool Rules

The best fantasy leagues are unique. Some accomplish this by building the league around a distinctive theme and others do it by scheduling an incredible gathering each year for their draft or giving an unbelievable prize to the winner. Personally, I feel that the rule book is the place to start when attempting to create a one-of-a-kind league.

Because there are contracts, player salaries, and a cap, salary cap leagues give commissioners the best platform to get creative with their rules. Over the years I’ve come up with a few that have gone over well.

Holdouts

This one isn’t all that unique anymore as many cap leagues have a variation in their rulebook but it’s still worth mentioning. Simply put, if the goal of your league is to put owners in a position to make the same kind of decisions NFL general managers make (which is an excellent goal), choosing a holdout (or group of holdouts) every off-season is important. The question is, how should you choose them?

I prefer to put the names of the top-scoring players at every position in a hat. (My leagues fill two starting lineups worth of players to choose from.) Draw two players’ names and those are the players holding out to be the highest-paid player at his position. Obviously, players that are free agents are ineligible to holdout, but it’s also fun to make players that haven’t yet played through their original rookie contract and players that recently inked an extension or were tagged as franchise players ineligible to holdout.

I also like to give the owner similar options to those of an NFL GM when a player withholds his services. He or she can either cave to the player’s demands, giving him a new contract at an elite salary, or allow the player to hold out, which means the owner doesn’t have to pay the player’s salary.

If the owner chooses to give in to the player’s demands, a new contract is awarded to the player and the holdout is over. But if the owner chooses to allow the player to hold out, there must be a way to determine if and when the player gives up his holdout and returns. Holding a simple weekly online dice roll where the owner must roll a ten for the player to return to the team does the trick in my leagues. You can also create some compromises such as, “if an 11 is rolled, the player returns for a yearly salary equal to 80% of the highest-paid player at his position.”

Restricted Free Agency

Restricted Free Agency certainly isn’t a new idea. Many leagues incorporate it. I just don’t think they’re doing it correctly.

In the NFL, restricted free agents are players coming off their rookie contracts. Their team attaches an RFA tag to them that indicates the round of the draft pick they’ll be forced to surrender should they sign the player away and the original team has the right to match any offer. Restricted free agency in salary cap leagues should mimic this exactly, with a few minor changes.

Each off-season, every player with an expired rookie contract is made eligible for restricted free agency. The team will have the option of tendering a contract to the player that will create both the compensation the team will receive should they lose the player to another team during the auction, and the opening bid another owner must start at to attempt to sign the player away.

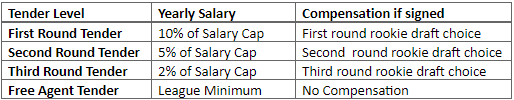

Tags could look something like this…

Once all the tenders have been made, there is an RFA auction where any owner can nominate any player (provided they have the draft pick compensation available as collateral.) Because there is sure to be quality young talent available in the auction, things get incredibly competitive and create some very difficult decisions.

I’ve also found that adding a “Duel First Round Tender” can add to the fun. Making the yearly salary 15% and the compensation a first-round rookie draft choice in each of the next two years can add another wrinkle.

Roster Exemptions

In leagues with a strict salary cap, meaning all or most of player salaries are guaranteed, the pressure to stay away from costly long-term mistakes when giving out contracts can be overbearing at times. That’s where roster exemptions come into play.

A roster exemption gives owners the ability to completely remove a player as well as the player’s salary from their roster and their salary cap without penalty. They’re incredibly valuable, which is what makes them such a great addition to strict cap leagues. To make them even more valuable, allow them to be traded.

Perhaps the best part about roster exemptions is that it opens up incredible strategic opportunities. Thrifty owners that can trust themselves to stay away from bad long-term contracts can use them as a trade chip to make a run at a title, rebuilders can trade for a horrible contract (along with something else) from a team without an exemption knowing they’ll use theirs on the player and be no worse for the wear, and owners in leagues that require you to bid both contract length and yearly salary can add the extra year to a contract offer without too much risk to add the missing piece to their title run.

Obviously, the softer the salary cap, the less valuable of an addition the exemption rule is but there’s no doubt, the rule can make all facets of a cap league more enjoyable.

Salary Reallocation

This is another one of my favorites but again, is really only a quality rule for leagues with strict penalties for dropping players.

Having extra cap space can be a great thing at some points in the season, like early on when you’re bidding on a hot free agent, and an awful thing at other times, like late in the season when the waiver wire is baron. Don’t you wish you could just move that cap space to next year? Salary Reallocation makes that possible.

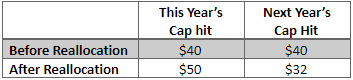

It’s simple really. The rule allows owners to pay part of a player’s future salary against the current year’s cap. So if you have $10 of cap space late in the year and owe your top wide receiver $40 next season ($200 cap), you can give him a bonus this year in order to get next year at a discount.

I always incorporate a cost to re-allocate a contract. After all, why would a player give you a break without getting something in return? So in my rules, it costs about 1% if the cap, going to the player as a “signing bonus.” Let’s take a closer look at the example from above.

Your WR1 has a $40 salary both this year and next before reallocating anything. You pay him a $2 bonus (making your cap space $8 for this year), move $8 of next year’s salary to this year, and presto! You make the most of being frugal.

I like to create a two-week window for reallocation at the end of the regular season. It makes contenders think twice about using all their space and gives rebuilding franchises an excellent way to start next year on the right foot.

Luxury Tax

The luxury tax is another rule that is really only a good rule for strict cap leagues.

If you’re a fan of Major League Baseball or the NBA, you know what it is. Essentially, owners can go over the salary cap by paying a tax. In my leagues, I set it at $10 (of real money) for every dollar they go over the cap.

You may not think owners would be willing to open their wallet for a $1 waiver wire add, but many in my leagues seem to do it yearly. It’s a good tool for owners in strict cap leagues when they’re up against the cap and have no choice.

If you’re wondering if owners ever go all George Steinbrenner with the rule, it’s never really got out of control. But if you’re worried about it, just put the tax on a sliding scale. So the first $5 over the cap cost you $10 each (of real money), the next $5 cost you $20, the next $5 cost you $30 and so on.

Bidding Salary AND Years

This is my favorite salary cap rule by far! I’m sorry in advance for the length.

Salary cap leagues with an auction followed by owners handing out contract lengths are fun, but far too often a group of savvy owners turn the auction into an endless list of one-year contracts, never risky a high dollar, long-term contract. This bidding process doesn’t resemble the NFL’s free agency in the slightest. After all, NFL general managers have to make a contract offer that includes both the yearly salary and the number of years the contract is for. Cap leagues should follow suit.

Many leagues that incorporate salary and contract length into their free agent auction use a bidding chart which is a great way to do it but my leagues do it a little differently. Instead, I created a set of rules that determines which contract a player prefers. They are as follows…

- Opening Contract Offer

- An Opening Contract Offer is made by the owner who nominates a free agent.

- The offer consists of the proposed yearly salary and the number of years the owner is offering the contract for. (example: $10/2 years)

- The Opening Contract Offer can be outbid by any other owner who makes a Qualifying Contract Offer.

- The “Basic Rules of Bidding” below apply to the opening contract offer.

- Basic Rules of Bidding ($200 cap league)

- All bids will be in even dollar amounts.

- All bids under $10 do not require the years offered to be announced.

- All bids for $1 will be a one-year contract offer.

- All winning bids of between $2 and $9 will give the owner an immediate option of giving the player either a one or two-year contract.

- All bids of $10 or more per year must include the number of years the owner is willing to sign the player to.

- Bids under $20 per year cannot be for longer than three years.

- Bids of $20 or more per year can go up to five years in length.

- Qualifying Contract Offer

- A Qualifying Contract Offer consists of the player’s salary per year and the number of years the owner is offering the contract for.

- The offer must be greater than the opening contract offer or previous qualifying contract offer.

- The “Basic Rules to Bidding” (found above) apply to the Qualifying Contract Offer.

- To be a Qualifying Contract Offer the bid must meet one of the following criteria…

- The bid must be for a higher yearly salary and equal or more amount of years than the previous bid. (Example: If the current bid is $10 for 2 years, a qualifying contract offer could be $11 for 2 years.)

- The bid must be for a higher amount of years and an equal or greater yearly salary than the previous bid. (Example: If the current bid is $5 for 2 years, a qualifying contract offer could be $5 for 3 years.)

- Or

- The yearly salary of a bid can only be lowered by offering a longer contract. Each additional year on a contract is worth $3 in yearly salary when bidding. (Example: If the current bid is $18 for 2 years, it can be outbid by bidding $15 for 3 years.)

- The number of years in a bid can also be lowered by doing the same thing in reverse. You just make an offer with a higher yearly salary. For every additional $3 bid, you can lower the number of years on a contract offer. (Example: If the current bid is $12 for 3 years, it can be outbid by bidding $15 for 2 years.)

- Once a bid reaches each $10 increment ($10, $20, $30, etc.) the yearly salary cannot dip below that amount.

- A bid cannot return to an amount that it has already been at. (Example: If a bid is at $17 for 2 years and is outbid by bidding $14 for 3 years. The next bidder will have to bid $18 for 2 years to get that year back off the bid.)

- Awarding a player to a Team

- Once a qualifying bid has been made on a player, the player will be awarded to a franchise when every other owner has had an opportunity to outbid the current offer and passed on that opportunity.

So there it is. Straight out of my rule book. I suppose I could translate those rules into a bidding chart but that removes a bit of the strategy in my opinion because the second bid always outbids the first one with the “$3 per year rule” and the plateaus at each $10 create even more strategic maneuvering.

More than anything else, this bidding system puts pressure on owners that closely resembles that of an NFL general manager. When you think you’ll be able to get an RB2 on a short-term deal only to see all of them get three-year offers, the pressure is on to either give in and extend the player out or pay a premium to keep the long-term risk down. None of that exists in standard auctions that allow owners to select the contract length afterwards.

Conclusion

That’s going to do it for my 11 part series, Salary Cap Confidential. If nothing else, I hope it got somebody interested in giving a cap league a shot. And if it gave somebody an idea for a rule change or a strategy to implement to better their team, even better! Nevertheless, thanks for reading and good luck in your cap leagues!

- League Tycoon: Dynasty Salary Cap Fantasy Football - December 15, 2023

- Final Dynasty Rookie Report Card: Wide Receivers, Part Two - March 22, 2023

- 2023 NFL Scouting Combine: Offensive Player Dynasty Review - March 10, 2023