Adjusting Draft Capital with College Production

We get better at things as we get older. Not all of us, and not all things, of course. But as a rule, it’s pretty great.

Practice and experience count for something, and so does how we grow. These are not outrageous statements or a something anyone would disagree with broadly. It’s also something we can support with large sample sizes and data, which is good because our own personal experience can mislead us. Applying this to fantasy football or the NFL is also not new. I couldn’t even tell you the first to do it. But the first person I really remember explaining the value of it and uncovering a simple edge most were ignoring because it didn’t fit narratives, was Jon Moore at rotoviz.com

I’ve written about age and production in college a lot before. Check out my previous articles on DLF. I’ve re-created the work of Moore and others on the subject because I want to use it. But I’ve also been looking for ways to represent and explain its use.

Stats and data can sometimes be described in a way that moves the conversation away from football. So I let’s be clear about what I’m saying:

1. What a player does on a football field – his production – matters

2. The difference in how fast we improve, as well as the difference in how we improve, matters

Who is more likely to score fantasy points in the NFL?

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

Before I try to explain what I think is going on, let’ see what I’m basing it on. Looking back on a 17-year sample size, I tested everything from athleticism to the difference between the yards and receptions a player caught in college and compared to the player who hit in the NFL.

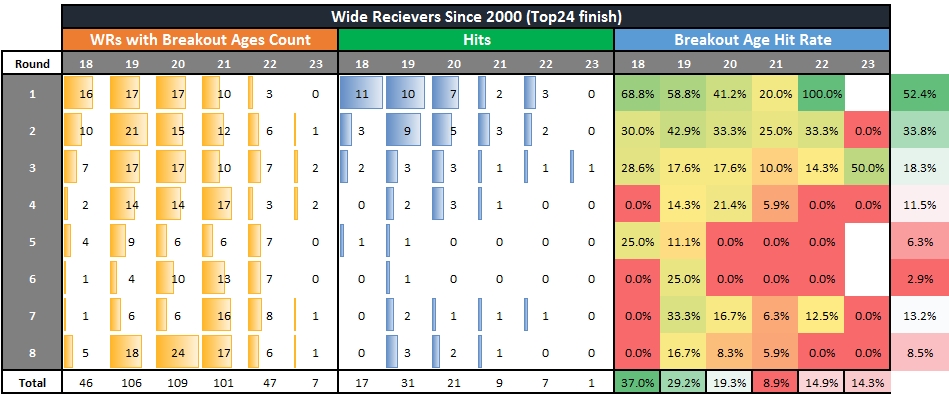

Draft capital is the clear best indicator of how players hit. 52% of all players who have finished in the top 24 since 2000 have been first-round picks. That’s not where we should stop, however, because we have more information. So, using breakout age, I want to see if there is a way to distinguish between players within each round.

Since 2000, over 37% of wide receivers drafted or undrafted with an age-18 Breakout Age have broken out with at least one top-24 PPR season. Compare that to the 33% of all second-round picks. One of those was a fifth-round draft pick, Stefon Diggs.

18-year-old breakout players break out more often than second-round picks by themselves. They also tend to get drafted in the first three rounds. This means their numbers have often been swept up by less precise draft capital breakdowns.

When you look at every rookie class since 2000 and parse the data out by how early players started to be the dominant option on their college team, the contrast is noticeable.

We can even out these sample sizes – the number of players drafted with each breakout age – if we combine some of these columns.

Breakout Age never beats draft capital. Only looking at these two things means that you should still draft first-round wide receivers before second-round receivers and so on. But using Breakout Age, we can judge between players within the same round more clearly.

In other words, a wide receiver drafted in the first round who breaks out in college before he is 20, is more likely to break out in the NFL than one who broke out after that age. That is true for every round of the draft.

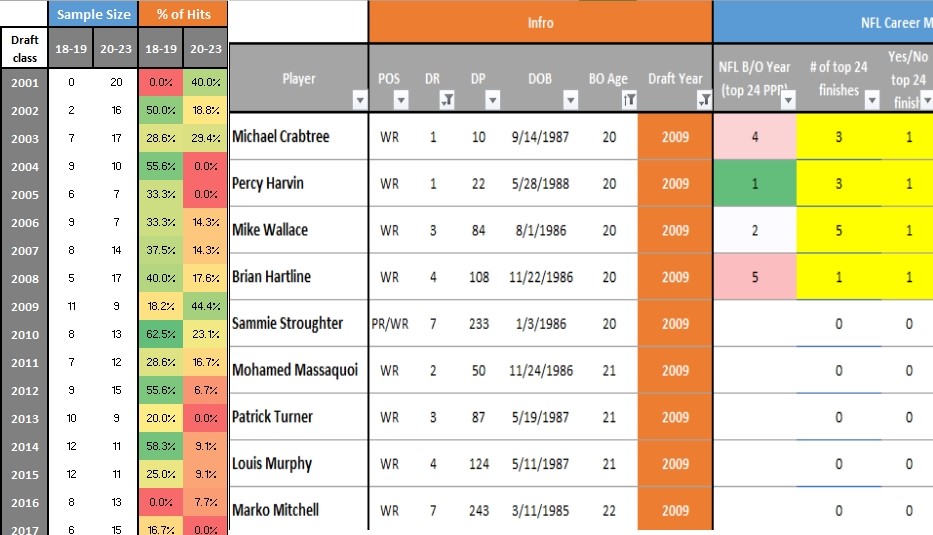

Each draft class is different. So let’s break it down by each separate draft class. This is only drafted players as well so there are no UDFAs included.

2009 is the only exception. This is the year Kenny Britt and Darrius Heyward-Bey were drafted with age-19 breakout ages and Michael Crabtree and Brian Hartline broke out after their third year in the NFL. Every other year, players who produced earlier in college were a more target-rich pond to fish in. You were more likely to hit a top-24 wide receiver within each round just by considering how early they produced in college.

The 2018 Class

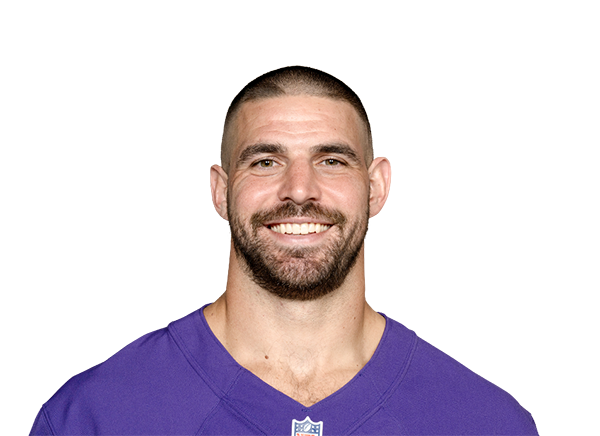

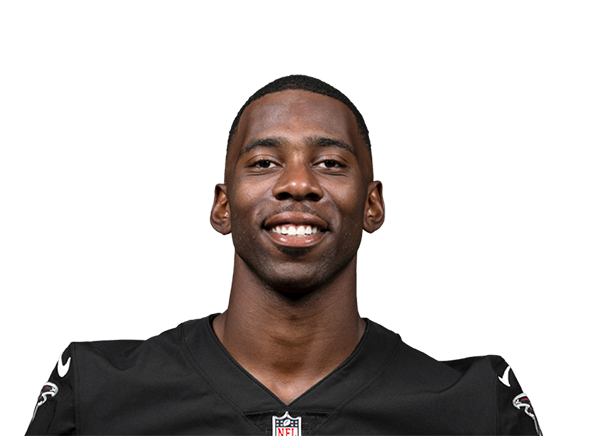

Looking at just the first three rounds of the 2018 class, the most likely to produce a top-24 wide receiver, here is how breakout age adjusts the rounds.

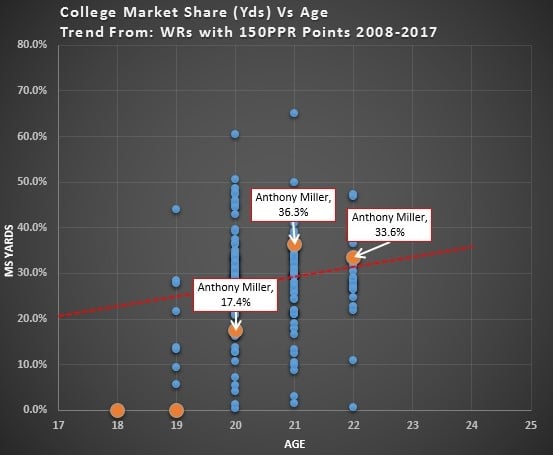

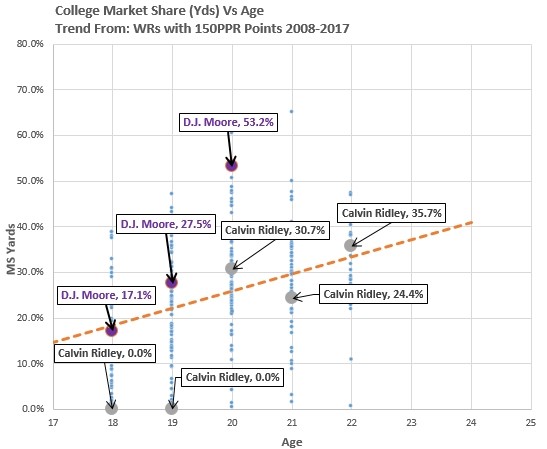

Does this mean I like DJ Chark more than Anthony Miller? Hell no. This isn’t the only thing I consider while drafting players. I do think it means Miller is in a less-likely-to-hit bracket based on history. But Breakout Age is just a proxy for how well a player produced adjusted for age in college. Calvin Ridley and Miller both overproduced well based on the average of successful NFL players since 2008.

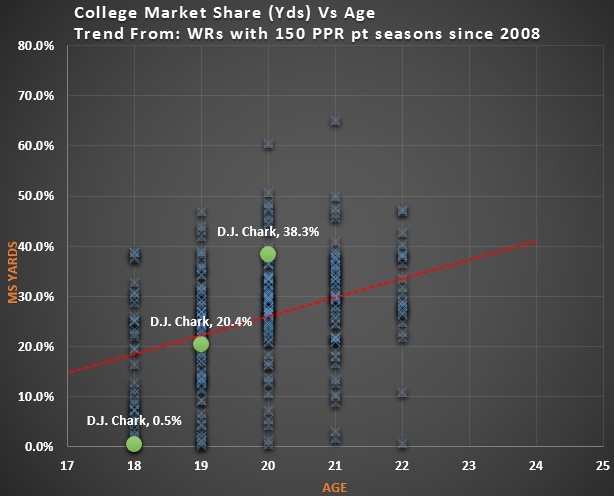

On the other hand, DJ Chark really wasn’t productive compared to successful NFL players until he was 20 years old despite playing at age 18 and 19.

Based on all of this information, I’ve ranked 2018 WR rookies this way:

We have to weigh the situation and individual talent on tape as well, of course, and I don’t have any problem taking Miller as the third or fourth wide receiver from this year’s class. I’ve taken Ridley whenever he drops below D.J. Moore and Christian Kirk in drafts as well. Mostly I think of this as a way to highlight when good rookie prospects are rising and falling in ADP.

Production mattering

Production matters. Physical traits and athleticism look good in a uniform. But if a player doesn’t catch the ball, if he doesn’t put yards under his boots, it doesn’t matter. Not because he can’t learn, but because football is a skill based game. If he hasn’t shown the ability to pick up all the skills that go into earning a target, and catching a ball, in college, it’s unlikely he’ll pick it up at the NFL level. Despite all our hopes and dreams, the NFL isn’t a developmental league.

I’m not saying athleticism doesn’t matter. There is a clearly definable threshold for athletic traits in the NFL. Frankly, you can’t be #good if you can’t at least keep up. But talent can come in a variety of forms. An average player with more speed is better than one with just so-so speed. But if that so-so player knows how and when to use the speed he’s got better, he’s going to win.

There is no easy way to represent who is producing more on a football field. The condition, supporting cast and competition varies from year to year and team to team. But there are things that can help us.

The best way to find out which players are actually better is to consider their production in relation to their overall makeup. Dorial Green-Beckham was the most athletic player on any football field he ever stepped on before the NFL. But he was 20 years old before he ever produced more than 20% of his college teams receiving yards in college. That means he had more experience, training, and athleticism before he could even be a productive player in college. That’s concerning. His athleticism didn’t make up for that as a prospect, it made him more questionable.

Hindsight is 20/20. When looking at players from a variety of different backgrounds – in different conferences against different competition with different levels of supporting casts – nothing is ever going to be very accurate.

However, looking back over the last 17 years, nothing tracks as well from college to the NFL as the player’s production adjust for age. Age-adjusted production is something we can use to make better guesses about which players with similar draft capital.

[/am4show]

- Peter Howard: Dynasty Fantasy Football Superflex Rankings Explained - March 6, 2024

- Dynasty Target and Regression Trends: Week 15 - December 23, 2023

- Dynasty Target and Regression Trends: Week 14 - December 16, 2023