Tracking the 2017 Rookie Running Back Class: Alvin Kamara

This article is one installment of a series in which I use my Observational Rushing Numbers to shed light on just how good the 2017 rookie running backs were at carrying the ball. You can find each previous article about these numbers on the series’s hub, including similar articles about Leonard Fournette and Joe Mixon.

I could spend plenty of words talking about Alvin Kamara’s meteoric rise. But that’s not the purpose of this article. In short: Kamara’s NFL career began as a third-round pick and, within one year, he rose to gain Offensive Rookie of the Year status and climbed into the first round of startup drafts. It’s incredibly easy to see why these two things happened: He ran for an eye-popping, league-best 6.1 yards per attempt and added 826 yards in the passing game. Today, I’ll be looking into the former achievement and examine how Kamara turned 120 carries into 728 yards by consulting my Observational Rushing Numbers.

(I’ve taken these tracking stats from Weeks 1-14 for each rookie running back with at least 75 carries. If you’re wondering what any of the stats mean in a fuller sense, check the series glossary.)

At a glance

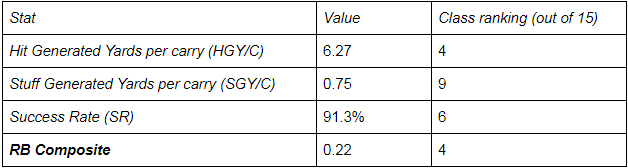

Four Big Stats and Class Radar

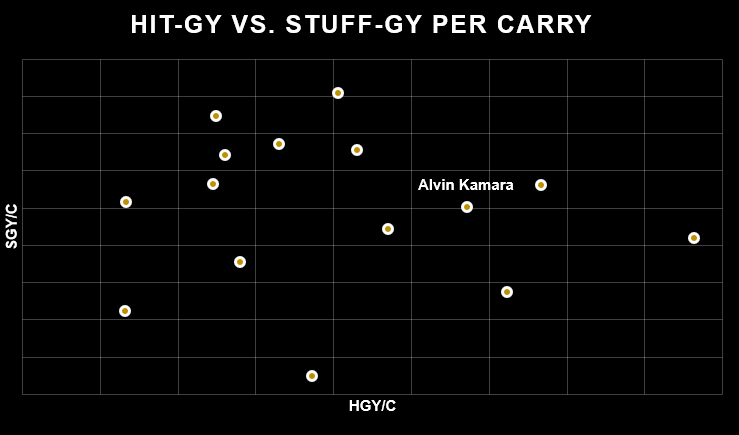

As the table and graph show, Alvin Kamara was basically a jack of all trades, master of none in the running game. He was perfectly solid at hitting holes (what Success Rate measures), which provided a level of consistency necessary to take advantage of what a superb offensive line (more on this later) offered. In terms of generating yardage, Kamara was both dangerous in the open field (what HGY/C measures) and above-average when left to his own devices (what SGY/C measures), despite ranking ninth in the class:

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

It’s quite difficult to be above-average in all three categories of rushing productivity — only Kareem Hunt and Dalvin Cook managed it, in addition to Kamara. As a result, the Volunteer-turned-Saint finished 2017 with the fourth-highest RB Composite score (which measures how well a back contributes to the rushing game, overall), despite middling finishes in the three component stats.

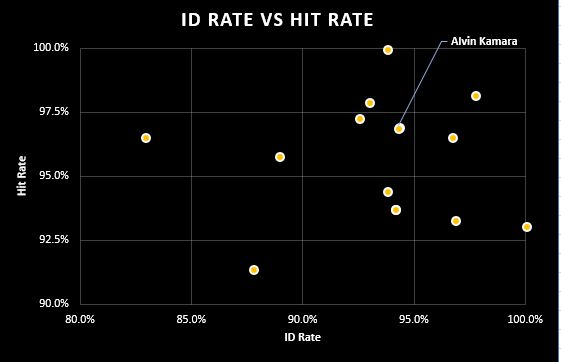

Success Rate

Frankly, some of Alvin Kamara’s stats are kind of boring, most notably when we look at his ability to hit creases. He was pretty good at identifying gaps that his blocking opened (measured by Identification Rate), pretty good at making it to and through the holes that he found (measured by Hit Rate), and thus, was pretty good at taking what his offensive line gave to him. All three stats can be seen together in the class radar graph in the previous section, and here are Kamara’s monotonously good Identification and Hit Rates:

Not the best, but certainly not bad.

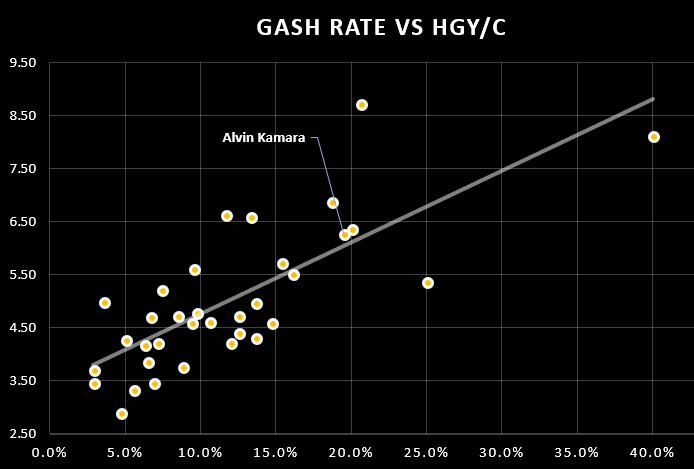

Hit Generated Yards

Where Kamara really began to set himself apart (in the running game) was, unsurprisingly, the open field. He finished with 6.27 HGY/C because of his Gash Rate (how often he generated at least 10 yards after hitting a hole) — third-best in the class, and the very best of all rookies with at least 100 carries. Zooming out even further, Kamara had one of the best Gash Rates of any back I’ve tracked, veterans included:

Judging by his proximity to the trendline, Kamara generated about as much as we’d expect him to, given how often he made splash plays.

There is some reason to pause in this open-field discussion. Kamara manufactured “just” 0.32 Broken Tackles per Hit (self-explanatory), barely above the rookie average of 0.31. Him finishing with such high Gash Rate and HGY/C marks indicates, to me, that he might have relied too much on athleticism, and not enough on dodging tacklers. Still, he proved that he was quite adequately shifty in the receiving game. Plus, even if he was overly reliant on his athleticism, that decision was not made in vain. Looking back through his 2017 film, his special physical traits allowed him to generate yardage that most backs couldn’t:

Ultimately, I don’t think there’s much reason for concern here.

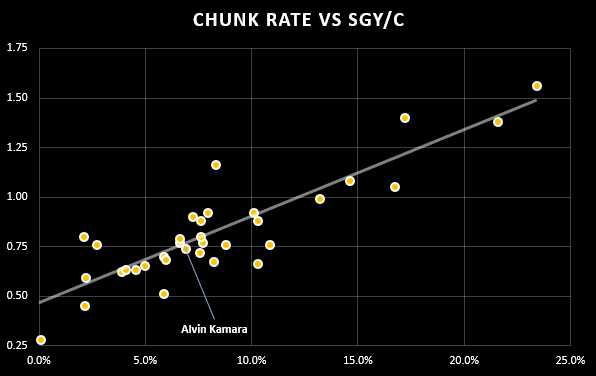

Stuff Generated Yards

The obvious weakness in all of Alvin Kamara’s characteristics is his size. He’s not big — though at 5’10”, 215 lbs, he isn’t the smallest guy either — so he has much more difficulty generating yardage in limited space than some other guys. Fortunately, he’s learned some of Christian McCaffrey‘s lessons in “how to create as a little guy around much bigger dudes.” Consequently, he finished a touch above average in SGY/C. Comparing that mark with his Chunk Rate (how often he generated at least three yards on stuffs) shows that that positioning was no fluke:

The good news, here, is that McCaffrey (among others) has shown that you don’t have to be a large human to produce well in tight confines; McCaffrey finished second in the entire class in SGY/C. Thus, there’s some room for Kamara to approach McCaffrey’s excellence. And it isn’t out of the question for him to do so, given that he’s already on the right track.

Run blocking

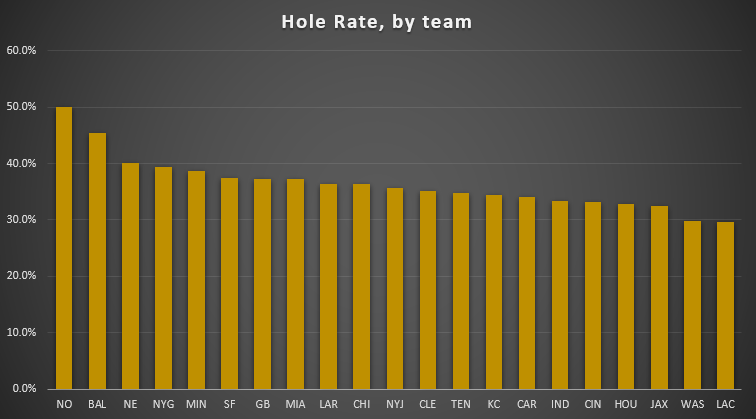

Three Big Stats

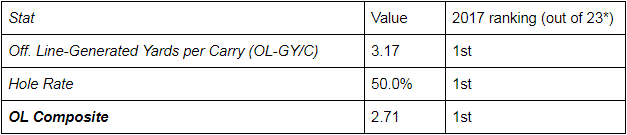

*I have tracked some veteran RBs already, and some teams have multiple rookies with over 75 carries, so there will be a difference between the rookie RB class’s 15 members and the number of offensive lines being ranked.

At some point, you were probably wondering how a running back who finished closer to “good” than “elite” ran for over six dang yards per carry. It’s simple! He just had to run behind an absurdly strong blocking unit. I have yet to track the Saints blocking for Mark Ingram, but even then, their offensive line is preposterously better than the rest of the units I’ve tracked. First, let’s look at how much better their OL-GY/C (how many yards any back could gain behind the blocking, on a per-carry basis) was than the rest:

The gap between first (New Orleans) and second (Baltimore) place is equal to the difference between second and 18th (Washington) place.

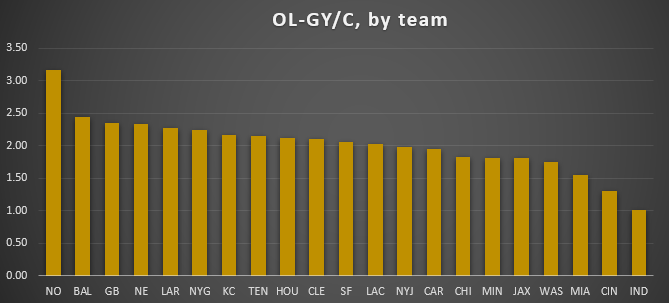

It wasn’t like they did a single thing better than the rest, either; looking at the proportion of carries in which the offensive line generated (x) yards, the Saints were clearly, consistently the best. They had the least runs (potentially) stopped in the backfield and the fewest runs (potentially) stopped before the second level (and thus, the most runs reach the second level), all shown by the Saints-colored line on this otherwise-messy chart:

(The blue line that was just as bad as the Saints were good? The Colts.)

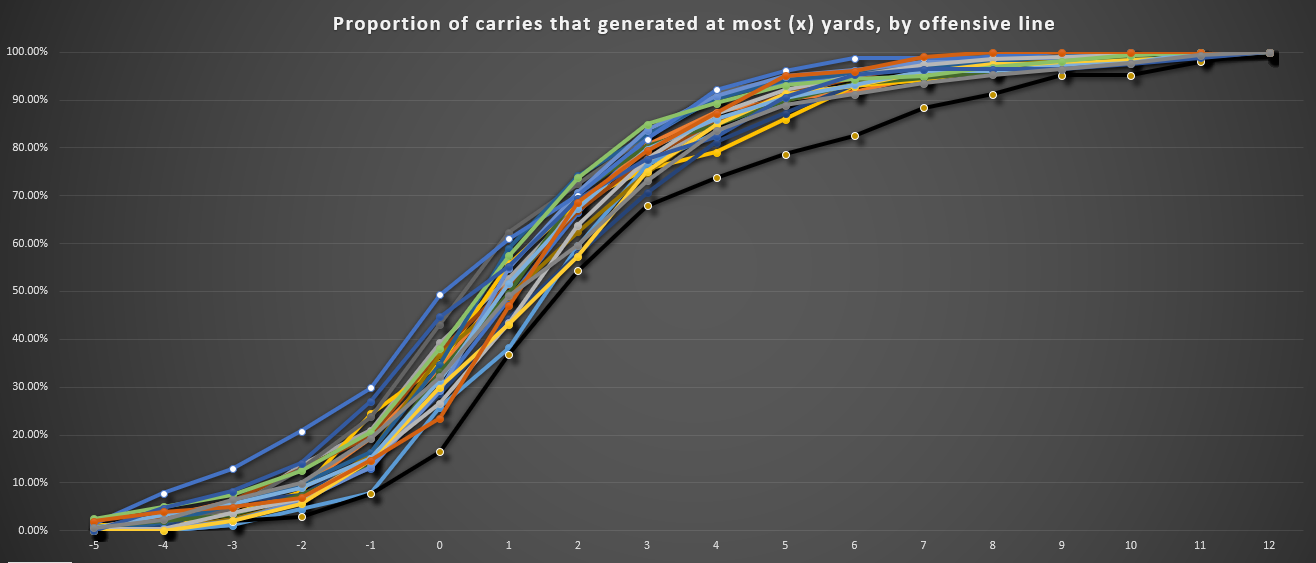

Now, let’s look at how much better their Hole Rate (how often they provided a back with opportunities to play in space) was than the rest:

Though a bit more muted this time around, the gaps between the Saints and second place, in both cases, are outlandish. It’s hard to overstate how well they blocked for Kamara.

With the help of our friend Tom Kislingbury, here are the players who delivered these results, by week:

Here you go pic.twitter.com/J5i85czsJL

— Tom Kislingbury (@TomDegenerate) June 30, 2018

As you can see, there were actually quite a few contributors. In fact, Pro Football Focus notes that the Saints put 18 different combinations together up front over 2017. But, there were a few mainstays: Andrus Peat, Max Unger, and Ryan Ramczyk played the lion’s share of snaps in virtually every Saints game last year. Larry Warford, Senio Kelemete, and Terron Armstead all logged snaps on at least half of the team’s plays, too.

Of those six, New Orleans returns all but Kelemete. Josh LeRiebus, a backup center who racked up 20 percent of snaps himself, is back. Jermon Bushrod, a two-time Pro Bowler for the Saints in 2011 and 2012, is also back after a few seasons with both the Bears and Dolphins. (I doubt he gets back to that Pro Bowl level, but you’d have to like him better than most of the league’s backups.) The Saints even added tackle Rick Leonard and center Will Clapp in the fourth and seventh rounds, respectively, of the NFL Draft.

There is talent, continuity, insurance, and proof of product in this unit. It’s hard to project 2017’s degree of brilliance without any regression in 2018 (especially considering how healthy the top three were), but it’s even harder to see them falling off very much. Good news, Saints fans and Kamara owners!

Conclusion

Alvin Kamara is a really nice ballcarrier in his own right, but the Saints offensive line really stole the show in 2017. It broke the charts in every statistical category. It is the reason that Kamara ran for 6.1 yards per carry.

Of course, none of this is meant to demean Kamara — he was very good in his own right. He did something that only Dalvin Cook and Kareem Hunt could also pull off. His Observational Rushing Numbers weren’t dazzling, but they were still some of the class’s strongest. To blow past 700 yards in 120 carries requires tons of skill from both the offensive line and the back.

Oh yeah, we also haven’t mentioned Kamara’s receiving game. He does stuff like this. That’s all I really think I need to say.

Alvin Kamara is a talent, and the Saints’ ecosystem makes his production special.

[/am4show]

- 2024 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Drafts: A View from the 1.03 - April 21, 2024

- Devy Fantasy Football: Top Five Quarterbacks - August 22, 2022

- 2022 Dynasty Fantasy Football Rookie Prospect: Drake London, WR USC - April 16, 2022