How Ownership Churn Affects Leagues, Championships and Dynasties

As dynasty fantasy football owners, we are inherently curious and drawn to light like moths to a flame whenever an article claims to have predictions for how our league will turn out. Unfortunately, for many of you, though, this article is tailor-made for those owners who work a little bit harder than the rest of us, take on more responsibility and get little-to-no thanks for the job they do. That subset of owners is, of course, the commissioners of our leagues.

I am a commissioner as well and run six different leagues, each composed of 12 owners and trust me when I say each owner is unique in his or her own way. There truly isn’t a magical “one size fits all” approach to dealing with owners. Some need constant attention (good or bad), some need to be left alone, some you actually want to leave alone, others are confrontational towards any authority, some are confrontational towards anyone, some don’t know when to throttle down and others never seem to ever throttle up. These are just a few of the nearly limitless personality types who can, and will, find their way into your leagues. Even if you’re not a commissioner, you’ve likely run into these people in the leagues you’re a part of.

I quite honestly don’t know why anyone would choose to be a commissioner and I can’t explain why I’ve willingly chosen to do something I can’t explain six times. Maybe it’s the fun of making a league how you want it to be or maybe it’s just the chance to meet some cool new people, who honestly knows? The list of reasons to start a league are likely as long as the list of different personalities I spoke about earlier in this article. Nonetheless, whatever the reason may be, a league lives and dies with its commissioner.

Unfortunately, fantasy writers do a disservice to these noble individuals. We don’t help to prepare them as well as we possibly could for the thankless job they volunteer to undertake. We focus entirely too much on the other owners – those with responsibilities that start and end with only their own team. We talk about how those owners can make their team better, but where are the articles which aim to help commissioners? There just aren’t that many.

Well, here’s my stab at it.

One of the toughest things to do as a commissioner is fill vacancies. You have to be equal parts used car salesman and nervous teenager introducing your significant other to your parents. On the one hand, you have to pull every trick out of the book in order to sell an item that someone else no longer wanted. While on the other hand, you have to make sure the new owner is prepared for, and accepted by, their new league mates. To be honest, it just isn’t a fun endeavor but every off-season most commissioners have to deal with this fiasco. So one of the most important things this article aims to do is to help prepare commissioners to either head off those owners thinking about leaving or to help commissioners be keenly aware of the turnover situation they can expect annually.

In order to achieve this unique goal, I had to gather some data (the foundation of any well written article in my opinion). In order to do this, I went to MyFantasyLeague.com (MFL) and went to their “Find A League” search option. In the search box I typed in “Dynasty” and hit search. The number of dynasty leagues out there is pretty staggering if I’m being completely honest. That simple search turned up 2,998 leagues and the season hasn’t even begun yet! To put that into perspective, at the end of last season (2014) there were 2,796 dynasty leagues, which means in the off-season dynasty has grown by around seven percent. If the current trend of 18% growth year over year continues to hold we can expect to see around 3,300 dynasty leagues on MFL alone by the end of next season.

The individual formats are growing as well, particularly IDP. This season there are already 70 dynasty leagues which identify themselves as IDP leagues in the title of their name, a 40% increase over the end of last season. Auction leagues have seen a 13% jump over last season growing from 27 at the end of last season to 31 with several weeks to go before the start of the season. Now, remember, not all leagues identify themselves as dynasty, IDP or auction in their name so the actual numbers are likely to be much higher than even represented here. However, in order to easily identify a league as one of these types this method was chosen.

So why am I telling you this?

[am4show have=’g1;’ guest_error=’sub_message’ user_error=’sub_message’ ]

Easy. Commissioners are facing competition to keep their owners on a very intense level. So many more options present themselves to your owners year over year. If they’ve made poor decisions with their team in the league commission, then they can now find a new league to begin over much easier than in years past. Think about this for a minute, if the 18% growth continues to hold true, by the end of this season there will effectively be twice as many dynasty leagues at that point then existed just four years ago. When success in the dynasty format is increasingly measured in three year windows, you can begin to see where some significant problems may arise.

Knowing the competition to retain owners is significant, perhaps wouldn’t it also be prudent to try to determine which owners you may face problems retaining? In order to help identify these owners I collected, what can only be described as, a ton of data on league dynamics – I obtained four years’ worth of data on 15 different leagues with similar set ups. These leagues were structured as follows:

- 12 owners

- Non-free, entry fees were required

- Non-IDP

- Non-auction

- Non-2QB

- PPR

- In existence for over four years

- Roster limits of between 24 and 26 players

- No Taxi Squad

- Retained Kickers and Team Defenses

- Six teams made the playoffs

You’d think there would be a lot of these leagues in existence but, truthfully, the dynasty format is so broad, complex and varied that it was increasingly difficult to find as many of these leagues as I would have hoped. I settled on 15 leagues being a nice round number and went about my data collection. This was an arduous task, in all honesty and ultimately encompassed 60 years’ worth of dynasty data. It took me the better part of a month to collect the data due to how I chose to set about pulling relevant information from the data. It’s not an exercise I hope to revisit any time soon.

First, let’s explore turnover in these leagues. As with any study of a population, I found subjects on either end of the turnover spectrum. One league saw eight owners leave one season while another league had only one owner leave in four years’ time. These kind of outliers are expected and help properly define a nice average we can depend upon. Ultimately, the average number of owners a commissioner can expect to leave his or her league on any given season is 1.91 owners, or roughly a two owner turnover. As annoying as this may seem to commissioners, turnover is present in nearly every ecosystem imaginable. The key, as with anything in life, is to keep it moderated. There is a fairly famous axiom which states that “Nothing can evolve without chaos, conversely, nothing can exist without defined order.” The remaining owners now have to deal with a changed dynamic which requires them to “feel out” and assess the new owner for how to best trade with and defeat them when playing against them. New owners can breathe new life into a league that has grown stale by bringing new perspectives, strategies and valuations with them. So the key here isn’t for commissioners to eschew turnover, but simply to try to control it as best as one can. Perhaps an owner just doesn’t fit or isn’t savvy enough to compete at the level that other owners do. In that case, a commissioner might be better served accepting that owner’s resignation at the end of the season as opposed to fighting to keep them. That same commissioner may be able to foresee this and could be working beforehand to line up a replacement owner in the event this occurs.

So, what happens when a new owner comes in?

If your experiences are anything like mine it almost always results in increased trading activity or, what is more affectionately referred as, a “fire sale.” The concept is fairly well understood and accepted as the new owner wants to shake things up a bit and reshape the team to reflect his or her own goals, objectives and desires. During this research, I observed 87 teams turnover at some point in the four year window. These owners likely had any number or reasons or justifications for leaving but more often than not the teams they left behind were near the bottom of their respectively leagues the previous year and were left in less than ideal shape.

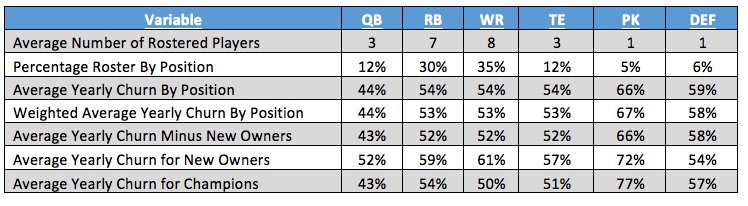

The new owners who assumed these teams, true to form, churned the players on their roster as a much higher pace than their league-mates. The average new owner saw a 52% change in their quarterback position over the previous year, a 59% change in their running back position, a 61% change at wide receiver, a 57% change at tight end, a 72% change at kicker and a 54% change at defense. Across the board, with the exception of the defense position, these percentages were usually five or more percentage points higher than the average owner which points to this effect being a real and observable trait of new owners. The positions that seems the safest on a new owner’s squad appeared to be quarterback and, strangely enough, defense. Meanwhile, kickers got blown out at a staggering rate followed, again strangely, by wide receivers. The new blood in a league clearly helps shake things up as the average new owner was able to bring their teams to a .480 average winning percentage. Not bad, all things considered, as one average they were actually able to field a competitive team in their first year of ownership.

So, how do these new owners compare to the average owner as a whole?

It’s not much differently than you might first expect. The common perception is that a dynasty is built on stability, a format that at its core is wildly different than the redraft format and requires patience and planning to build a team exactly how you want it. In reality, dynasty appears to be not all that different than redraft when you look at the yearly churn rate present on your average owner’s roster. The average owner churned their quarterback position at a 43% annual rate, their running back position saw a 52% change, their wide receiver position also changed 52%, their tight end position saw a 52% churn as well, followed by kickers at a 66% change rate and their defenses churned at a 58% clip. Only quarterbacks barely missed the unanticipated 50% over churn club.

What if we weighed the churn heavier for teams with better all play winning percentages? Maybe that could tease out some insight regarding which positions should be churned more or less? As it turns out, this doesn’t appear to point any moves that separate a winning team from a losing team, as all weighing the average did was move each position up or down one or two percentage points, nothing to point to an “Ah Ha!” moment.

I have to be honest here, when I first saw the average churn numbers I was absolutely shocked, but upon thinking about it a bit more several factors appear to have come into play here. First, the rookie draft requires teams make room for their rookies at the expense of players currently on their team. Second, waivers allow teams to constantly remold their rosters based on need, injury or potential. Finally, trades allow for further reshuffling of rosters. The key point to take away here is that despite a seemingly static format, dynasty is, in reality, an extreme fluid format that allows owners to fully remake their teams in very little time if desired.

Something I pondered while performing this research was, “What exactly is the composition of an average team?” Well, the average team breaks out like this, three quarterbacks (12%), seven running backs (30%), eight wide receivers (35%), three tight ends (12%), one kicker (5%) and one defense (6%). First, to clear up a couple of things, the difference in percentage points between kickers and defenses is due to rounding and is not actually a mistake. Second, the numbers don’t add up to between 24 and 26 (the roster limit range of the selected leagues) but this is due in large part to a lot of teams dropping either all their kickers, defenses (or both), which pushed the totals down.

So if an average team churns their roster so often, how do they take the next step towards becoming a champion? Also, once a team is a champion how does one stay there and truly achieve a true dynasty?

First, let me dispel this notion for you – teams rarely establish themselves as a dynasty. Of the 45 playoffs examined (2012, 2013 and 2014, examining 2011 wouldn’t have allowed for an accurate observation since the 2010 season would to have been observed to measure churn in that season as well), only three teams were able to repeat as champions (6.7% of all champions and 1.7% of all teams observed) and no team was able to reign as champion for three years straight. However, back to the original question, what does a champion do that is really all that different than an average team? As it turns out, aside from their winning percentage, which clocked in at .700, not that much.

Championship teams actually churned their rosters at a fairly comparable rate to everyone else. Their quarterbacks were swapped out at a 43% rate, their running backs changed 54% year over year, their wide receivers churned at a 50% rate, their tight ends changed 51% each year, their kickers changed 77% and their defenses churned at a 57% rate. Save for the kicker position, a champion churned each position no more than a two percent difference from the average team. The odd fact here is you would expect average teams and champions to be at least measurably different from one another, either the average teams would churn more often to try to “find the right mix” or champions would churn less in an effort to keep the team they have. However, that theory appears to be invalid.

Maybe championships are, for all intensively purposes, just flukes. The chances of a repeat champion (6.7%) versus the chances of any team winning a championship in any given year (8.3%) seem to suggest that championships may have a lot more to do with luck than what all champions wish to admit. Could luck be actually masquerading itself as skill this whole time? As it turns out, no.

In order to investigate this further, I took a look at how often a championship team was able to return to the playoffs. If luck were the motivating force here, we would expect a number that would fall right around 50%. As it turned out though, that number was actually much higher, an incredible 82% of championship teams were able to return to the playoffs the following season! This clearly indicates that, while luck may play a bit of a factor in obtaining (or even retaining) a championship, skill appears to thankfully rule the day.

In the end, the interesting dynamic to take away from this research could be that the level of churn introduced from new owners could possibly be just enough to tip the scales against champions repeating. However, even in the absence of new blood, the level of churn inherent in dynasty leagues via waivers, trades and the rookie draft appear to work against champions as only between one and two percent of teams will ever get to refer to themselves as a true dynasty.

Below is the data formatted in a more structured manner for those interested:

Finally, thank you to all the commissioners out there. Without you we all wouldn’t be able to enjoy the game we love.

[/am4show]